As I write this Sunday afternoon in April of 2020, the Corona virus continues to threaten global citizens without discrimination, killing the wealthy, the poor, the famous and the unknown. Despite the universal danger, a resurgence of nationalism has made some populations far more vulnerable to the deadly virus. Fernand de Varennes, the UN Special reporter on minority issues, stated recently: “Covid19 is not just a health issue; it can also be a virus that exacerbates xenophobia, hate and exclusion.” A recent UN News article reported that marginalized groups, including Asians, Roma, and Hispanics have been targeted with violence; those detained or incarcerated have been denied access to medical care, and some world leaders have fanned the flames of xenophobia, seeking to cast blame on ethnic minorities in order to prolong and expand their own political power. As politicians target minorities with hate speech, the survivors of the Holocaust have important testimony for our own era. At a time when multiple news outlets have reported that the history of the Holocaust is fading from public memory, a new book from Prospect Park books is a timely and important reminder of the dangers of hate speech.

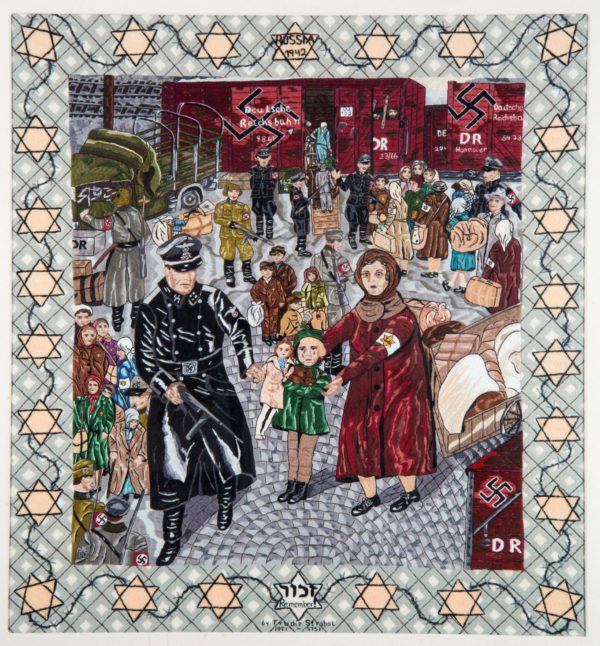

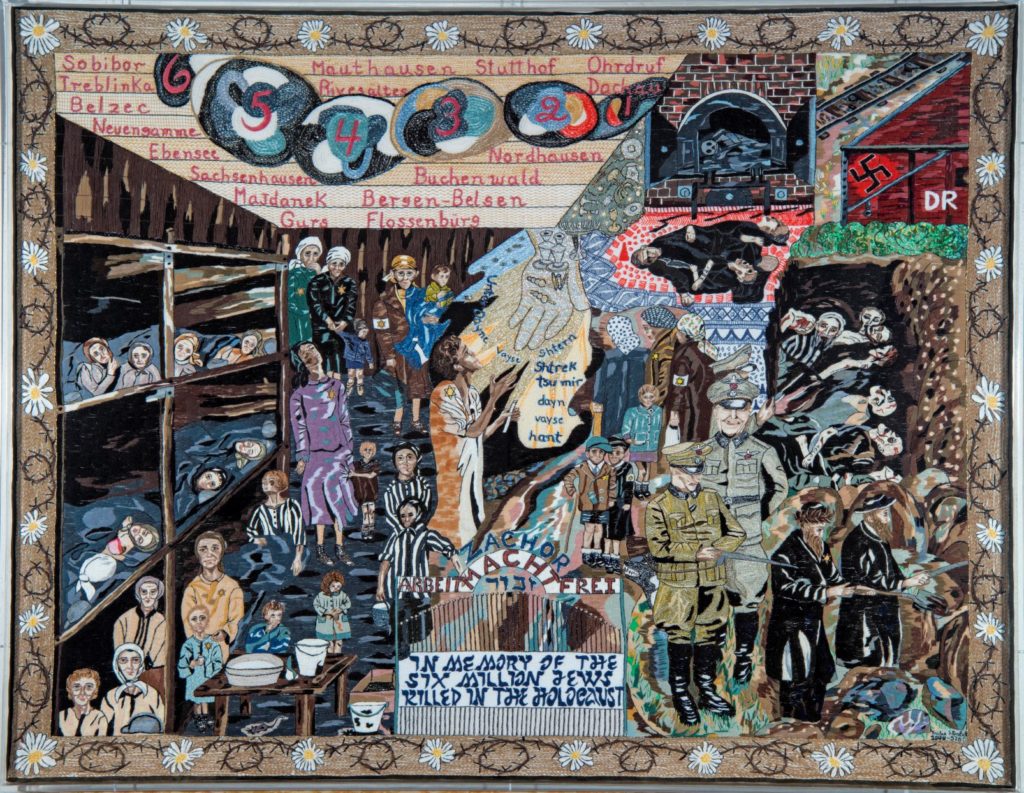

Stitched & Sewn: The Life Saving Art of Holocaust Survivor Trudie Strobel, by Jody Savin, humanizes the consequences of xenophobia, by following the trajectory of its impact on a single child over the course of her life. Trudie Strobel’s memories of the atrocities she endured are conveyed through the powerful medium of her embroidered murals. The story of Strobel’s survival and her eventual evolution into a recognized artist of Judaic embroidery gives readers hope in a time of despair. Recognizing the importance of Strobel’s artistic testimony, author Jody Savin located tapestries that Strobel had given away or sold, and interviewed Strobel. By framing the retrospective sequence of each tapestry within the historic and personal context of Strobel’s life story, Savin has preserved historic, important testimony of one of Los Angeles last surviving witnesses of the Holocaust. This important work, published by Prospect Park Books, allows readers to follow Strobel’s path to survival in a profound and visual journey.

The book begins in 1937, on the collective farm in Russia where Strobel’s parents, Vassiliy and Masha Labuhn, awaited Trudie’s birth. Vasilliy had been warned that his stature in the community would not protect him from arrest. When his Jewish co-workers and neighbors began to disappear, arrested in the middle of the night and taken away, Vassiliy spent an extravagant sum on a doll for his unborn daughter, a gift to remember how much her father loved her. Vassiliy’s premonition proved correct. Weeks before Trudie was born, he was arrested by the Soviet police, taken from Trudie and Masha, never to be seen again.

Four years later, Masha too was arrested and deported with Trudie, now four years old. In the chapter, “The Walk,” Savin conveys the horror of the 394 miles of the forced march from Russia through Poland. When prisoners were ordered to wear the Magen David, the yellow star of David, Masha helped sew them onto prisoner’s coats. Seeing Masha’s skill with the needle, a Nazi guard ordered Masha to repair his coat, a job that proved fateful in the coming days.

They walked through towns decimated by murder: Uman, where 10,000 Jews were killed in a year, where 1000 Jewish children had been massacred only two months before their arrival. One of their companions tried to save a precious Samovar, a symbol of the life she hoped to preserve. But she was beaten to death in front of Masha and Trudie by the same guard who had demanded the repair of the coat. In Lwow, thousands had been killed and tens of thousands sent to the Janowska death camp. It was here that young Trudie, waiting for orders, was approached by an SS guard.

Seeing the “Papa doll” in Trudie’s arms, he snatched it away. “Give that to me.”

Knowing of Trudie’s distress, Masha quietly but sternly warned her daughter, “Shah. Quiet! Don’t cry!” Masha knew how dire the consequences were.

The four-year-old Trudie buried her pain in silence, too terrified to cry. But the memory of this moment, when a four-year-old understood that she might be killed if she cried out, did not disappear. Instead, the indelible loss of the doll, symbolizing her connection to her father, haunted her dreams. For years, she had nightmares about dolls, as the event became a pivotal symbol of the loss of her freedom and the father the Stalinists had killed.

When the caravan arrived at the Lodz ghetto, they reached a place where 43,500 Jews would die of starvation and disease, and from which 77,000 would be sent to Chelmno, a death camp, between 1941 and 1944. But Masha’s sewing saved them. The Nazi guard had bragged about his coat; word of Masha’s skill had been passed. Guards located a sewing machine and put her to work.

The next transport put Masha and Trudie into a cattle car, crammed with other prisoners, reeking with vomit and the stench of human waste, with barely enough air to breathe. When the rest of the prisoner caravan left Lwow on a train to their own exterminations, Masha and Trudie were ordered into a separate train that was almost empty, destined for a Labor Camp. This satellite camp was an SS farm. Though prisoners were not immediately gassed there, many were worked to death.

Masha and Trudie sewed to survive. When the camp was liberated in 1945, Trudie was seven years old.

Though American immigration policies prevented Trudie and her mother from coming to the United States for another six years, they finally arrived in 1951. In Chicago, Trudie met and later married another Holocaust survivor, Hans Strobel; together they raised two sons. But when Strobel reached her fifties, the trauma of her wartime experiences caused a paralyzing mid-life depression. After a therapist suggested that she try to recreate the doll she had lost as a way to heal, needle and thread again saved her from despair. Recreating her doll led to a project called Eleven Centuries of Degradation, which is currently in the permanent collection of the Los Angeles Museum of the Holocaust. Strobel dressed 11 dolls in the historic costumes different countries used to stigmatize Jewish women throughout the centuries. Strobel’s dolls continue to educate thousands of visitors to the Museum. Continuing her path to recovery, Strobel began to work on embroidered murals, and slowly, stitch by stitch, began to free the childhood sorrow she had buried within her.

Strobel’s tapestries remind us to feel the deep wounds of the past. Each tableau in Stitched and Sewn provides crucial and vibrant testimony of the dangers of xenophobia. Strobel’s compelling testimony demonstrate art’s power to heal, and by showing how one artist overcame the virus of hate she endured, the book offers a message of hope. At this historic moment of global crisis, Strobel’s art and life story call us to remember the danger of losing our humanity in a time of crisis.

A recent ABC news headline reads:” FBI warns of potential surge of Hate Crimes against Asian Americans.” Crucially, the FBI mention warns of the violence fueled by political rhetoric: “Many Americans, including President Donald Trump and other political leaders and media commentators, have adopted the practice of calling the ailment the “China virus,” or some other variant that makes reference to China or Wuhan, rather than “Coronavirus” or “COVID-19,” the terms used by federal health officials and in the FBI analysis. The rhetoric, critics say, has fueled ill will and has led some people to act out against Asian Americans.” The FBI report refers to several examples, including the March 14 attack on a family trying to shop for supplies at a Walmart in Midland, Texas: “Three Asian American family members, including a 2-year-old and 6-year-old, were stabbed … The suspect indicated that he stabbed the family because he thought the family was Chinese, and infecting people with the Corona virus.”

As our world responds to the moral tests of the coronavirus ahead, Strobel’s testimony of her experiences during the holocaust has never been more relevant.

A child survivor of the Holocaust, Trudie Strobel settled in California, raising a family and never discussing the horrors she witnessed. After her children grew up, the trauma of her youth caught up with her, triggering a paralyzing depression. A therapist suggested that Trudie attempt to draw the memories that haunted her, and she did–but with needle and thread instead of a pencil. Resurrecting the Yemenite stitches of her ancestors, and using the skills taught by her mother, whose master seamstress talent saved their lives in the camps, Trudie began by stitching vast tableaus of her dark and personal memories of the Holocaust. What began as therapy exploded into works of breathtaking art, from narrative tapestries of Jewish history rendered in exacting detail to portraits of remarkable likeness. Many of her works are now in public and private collections.