During my four decades as a film journalist, I mostly interviewed movie actors and directors, but I also met artists, musicians, photographers, screenwriters and novelists. Among the writers I spoke with were Charles Bukowski, Michael Crichton, Norman Mailer, Sidney Sheldon, and Ray Bradbury, who was my favorite.

Bradbury (born August 22, 1920, died June 5, 2012) published his first collection of short stories, The Martian Chronicles, in 1950, and his work continues to be relevant today. On May 12, Farenheit 451, a TV movie by Ramin Bahrani (99 Homes), starring Michael B. Jordan, Michael Shannon and Sofia Boutella, based on Bradbury’s 1953 novel about a future society where books are forbidden and burnt by policemen-firemen at 451 degrees, premiered at the Cannes Film Festival. It airs on HBO as of May 19. The director comments: “The world is frighteningly catching up to what Bradbury had envisioned.”

You may watch trailer here, read review here.

For the history of book-burning, you may read this article from TIME magazine.

I just took the actual book, Farenheit 451, out of one of my many bookshelves and plan to read it again today.

Michael Shannon, Michael B. Jordan-Farenheit 451 © Michael Gibson/HBO.

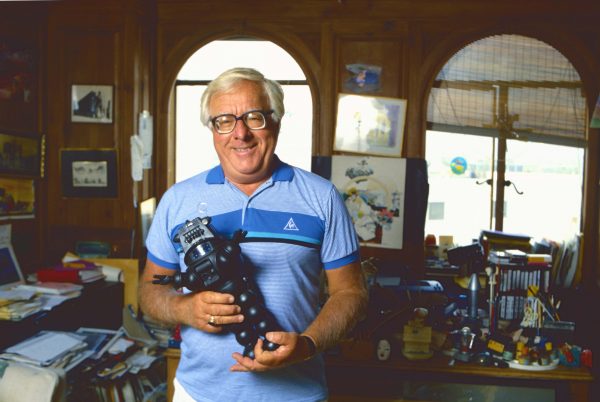

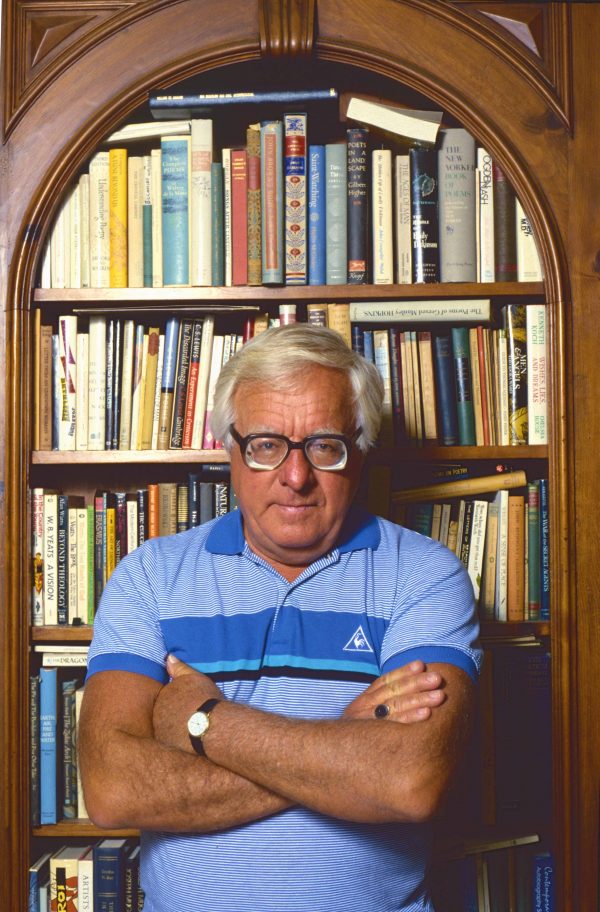

We share excerpts from my interview with Ray Bradbury, conducted at his Cheviot Hills home in September 1988, when The Toynbee Convector was published.

For the complete text and more photos, click writer, Ray Bradbury, in Elisa Leonelli, Photojournalist, at the Claremont Colleges Digital Library.

*

One of the biggest figures in science-fiction literature, Ray Bradbury has written novels, Farenheit 451 (1953), Dandelion Wine (1957), Something Wicked This Way Comes (1962), Death is a Lonely Business (1986), and collections of short stories, like The Martian Chronicles (1950), The Illustrated Man (1951), I Sing The Body Electric (1969). Now he is presenting another book of stories: The Toynbee Convector (1988).

Q: In the first short story of The Toynbee Convector, you describe a time traveler who goes 100 years into the future and comes back to report that humanity has made it. “We rebuilt the cities, cleaned the lakes and the rivers, washed the air, saved the dolphins, stopped the wars, moved to Mars, cured cancer and stopped death.” Are these your wishes for the world?

A: Sure. I hate doom-ridden, negative people; they don’t allow things to be done. I don’t criticize a problem if I have no answer for solving it. You have to immediately plunge in and cure it, if you can. Some situations can’t be solved, you just have to wait and hope. I try to offer my solution, when there is an immediate chance of doing it, like in rebuilding our cities. I know I can do that, with people like John Jerde, the architect who told me he had designed the Glendale Galleria around my concept, resocialize mankind, make people happy with a city that works right. By bringing people into the streets again, as in Paris, you cut down on the crime rate; it’s harder to commit a crime if people are watching you, so cities are safer if they are social. I have a plan to sew together all the areas of downtown Los Angeles and make it work again. The answer is pathways between them, with lights and street vendors, from Little Tokyo to Olvera Street to Chinatown along the Los Angeles River.

Q: You wrote screenplays, like Moby Dick (1956) directed by John Huston, and some of your books have been made into films, like Farenheit 451 (1966) by Francois Truffaut and The Illustrated Man (1969) with Rod Steiger and Claire Bloom. What do you like most about the movies?

A: I love the pure images of the medium, they elicit an immediate response from the viewer without using words, the great scenes of the most memorable films have stunning visual clarity. When you look at certain Fellini films, there are moments that have nothing to do with language, just images, like in Amarcord, where the Rex goes by at night, this big cliff of sea-going ship with all these peasants in rowboats looking up at it. It breaks your heart; just talking about it, I get chills in the back of my neck. Fellini films are so full of moments of beauty for the eye and the mind, that’s poetry. Fellini and I have very similar backgrounds, that’s why I love his work, our love of comic trips and film shows in what we do.

Q: Do you accept the label of science-fiction writer?

A: No, it’s so narrow, it would be like calling me a horror writer—I’ve done that too. Science fiction is a small part of my work, I’m a writer of ideas. I read Bernard Shaw or Shakespeare for inspiration, not science-fiction when I was growing up. I found it a bore, they had to explain how to build a rocket, who cares? Tell me why I should build a rocket, that’s different.

Q: What are the most important themes in your work? Space, time travel, magic, monsters, machines?

A: It’s hard to say, because, as a writer, you shouldn’t know what you’re doing, your intuition should lead you; only when you’re finished, you’ll see what you’ve done. I write stories to rid myself of certain fears, it’s a constant theme in many of my books; so one by one I take the scaly toads off my head and skin them, nail them to the wall, then I pick up the next nightmare and I run with that. Or I do stories of exhilaration and love and celebration, or stories about space travel, and why we’re here and why we should behave better, give back the gift.

Q: Do you consider yourself an optimist?

A: I don’t call myself an optimist, but an optimal behaviorist, I believe in living to the top of your capacity, of your genetic ability, throughout your life. If you behave optimally, year after year, you have all the things you’ve done accumulate around you and they become your teachers. You’ve always got yourself, and that makes you feel good, that you have done all this, that you haven’t refused to behave.

Q: Do you believe there is other intelligent life in the Universe?

A: Sure, it’s all over, but it’s far away. We are here, we are intelligent life, we are proof of the question. The Universe is forever, there are billions of suns and planets and civilizations out there, but I very much doubt if we’ll ever meet, the distances are too great. That means we have to be responsible to our planet in our corner of the Universe.

Q: Do you have religious beliefs?

A: Yes, I’ve written much religious poetry, but I don’t belong to any groups, political parties or organized religions. I’ve got to be free. I believe we ourselves are the representatives of the life force. George Bernard Shaw wrote about this, the Universe is using us as tools. If God is the Universe, and indeed he is, what’s the use of having it, if nobody can see it? You then create creatures like ourselves, privileged, intelligent beasts, to admire it. God put us here, so we could see and hear and smell and taste an touch Him/Us. The word religion only means “to relate to,” to try and make sense of the facts of existence.