Power and Pathos: Bronze Sculpture of the Hellenistic World

The J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles through November 1, 2015 and National Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C. from December 6, 2015 to March 20, 2016.

This is an exhibition the calibre of which is seldom seen in Los Angeles. As Dodge Thompson, Chief of Exhibitions at The National Gallery said, “This is a once in a lifetime exhibition.”

The magnificence of this exhibition must be viewed as a reflection of the amazing quality of sculpture in the Hellenistic era, whether bronze or marble.

Hellenistic not Greek!

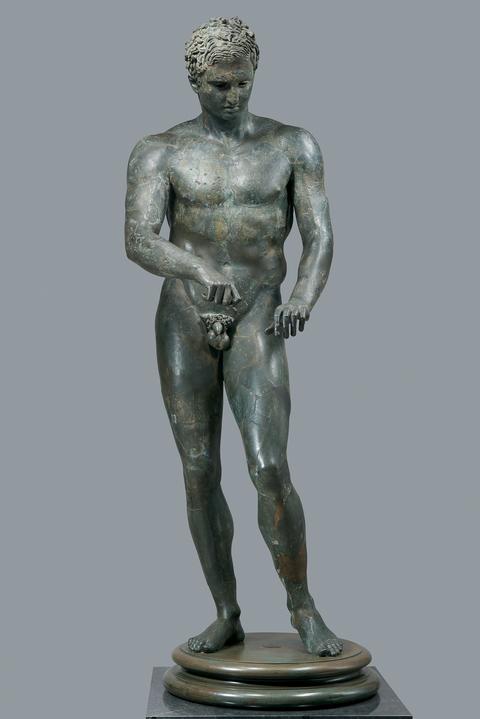

It is important that this distinction be made at the outset. The Hellenistic period is defined as the 300 years between the reigns of Alexander the Great of Macedon (336 – 323B.C..) and Augustus, the first Roman Emperor (31B.C. – A.D.14.). Alexander’s empire stretched from Macedonia in the Eastern Mediterranean, along the North African coast to India and Afghanistan. He conquered the extensive Persian Empire, quelled revolts and established new cities, Alexandria in Egypt, circa 331 B.C., one of the most prominent and enduring. Hellenism embodied the creation of new Greek cities in conquered lands. These settlements were both military colonies and entities in which the culture was strongly Greek, emphasizing language and political institutions. Common to all settlements was the gymnasium – an institution promoting physical and intellectual culture. Within these new settlements, there was coexistence of conquered and conqueror cultures; however, Greek culture remained dominant. Most of the individuals depicted in this exhibition appear to be coherently Greek; however, there are portraits of people with strikingly different facial characteristics who could be from conquered lands. Although bronze statues were ubiquitous across the Ancient Hellenistic Empire, few have survived. Most suffered the indignity of being melted down to provide raw material that would be utilized for mundane purposes. Those surviving have been rescued from sunken ships or excavated from subterranean hiding places. Although stylistic associations with certain sculptors and schools are possible, it is often difficult to determine geographical origin.

Today, we admire these statues as significant manifestations of a society that has long since vanished from the face of the Earth. We also recognize them for the aesthetic quality that they engender. They represent the canon of realistic representation that has long guided sculptors of the Western European tradition in their depictions of the human body and its accompanying physiognomy.

Utilizing bronze as their medium, these sculptors commanded it at a level of dexterity that has not been surpassed, and seldom equalled. As Andrew Stewart states in the exhibition catalogue, “In ancient Greece, bronze had a unique status. It was the metal from which the men that preceded the heroes were made, and the one that both gods and heroes had overwhelmingly employed for everything from palaces and fortifications to chariots, armor, weapons, vessels, tools, utensils and even jewelry … Bronze is hard, strong, resilient and flexible, and a body made of it naturally takes on some or all of those attributes in the observer’s mind … as Homer’s epithets emphatically suggest, its aesthetic appeal is equally, if not more a function of finish, where not one but three factors are at issue: tooling, patina and polychromy.”

Our principal knowledge and appreciation of ancient Greek sculpture emanates primarily from two sources: original Greek stone and bronze statues and Roman replicas of original Greek stone and bronze statues. Bronzes might have been as ubiquitous as marbles in Ancient Greek and Rome, however, their propinquity was diminished over time. In addition to presenting classic images of this genre, the exhibition reestablishes a long lost continuity.

If one were to seek a paradigm among all the sculptures presented, it would be ‘Statue of a Seated Boxer” from the Third Century B.C. As stated in the catalogue, it “… is among the most famous works of ancient sculpture and exemplifies Hellenistic art like few other masterpieces known today.”

When on view at The Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York, journalist Gay Talese recorded this appreciation.

[embedvideo id=”cHgrqOIXoN8″ website=”youtube”]

Ancient Romans were dedicated admirers of Greek art and culture. Throughout much of the Roman Empire, both Greek and Roman sculptors produced quantities of sculpture used to decorate upper class villas. Patronizing immigrant Greek doctors and sending their children to be educated in Athens, were further manifestations of Roman admiration for Greek art and society.

For some of us, our appreciation of Greek sculpture has been enhanced by two iconic marble statues: the Classical Apollo Belvedere, which resides in a private niche at the Vatican Museum, and the Hellenistic Victory of Samothrace, which commands the pinnacle of the grand staircase at The Louvre.

The Apollo is thought to be a Roman copy (circa 120-140 A.D.) of a lost bronze Hellenistic original made between 350 and 325 B.C. by the Greek sculptor Leochares. It was rediscovered in Central Italy in the late 15th century and much admired by Italian Renaissance artists who wanted to retrieve the aesthetic of the Ancient Greek and the Roman Empires.

The Winged Victory of Samothrace, is a 2nd-century B.C. Hellenistic marble sculpture of the Greek goddess Nike. It was created to not only honor the goddess, but to honor victory in a sea battle. The sculptor is thought to be Pythokritos of Rhodes. Discovered by a French consular official/archaeologist in 1863, it has been prominently displayed in the Louvre since 1884. The magnificence of this exhibition must be viewed as a reflection of the amazing quality of Greek sculpture in the Hellenistic era whether in bronze or marble. Following are some of the masterpieces to be seen in The Getty exhibition.

Prior to being seen at The Getty, this exhibition was presented at the Palazzo Strozzi in Florence.

[embedvideo id=”-zJp6wFXUYk” website=”youtube”]

When this exhibition is dismantled and objects are returned to their owners, an epic moment in art historical presentation will vanish. For some inexplicable reason, recently, there were several exhibitions of similar nature, but not on the same scale, occurring virtually simultaneously in Florence, Milan and Venice.