The My Celluloid Antidepressant series — which began with the irresistible Irish charmer, Sing Street, has now taken on added meaning as we adjust to the new normal vocabulary of “shelter in place,” “self quarantine” and “pandemic.” There is no longer a need to be depressed, anxious, or have any other psychiatric condition to take advantage of this energetic, kinetic and joyful Beatles film. Please read my little piece, and stay safe, sane, healthy (not necessarily in that order).

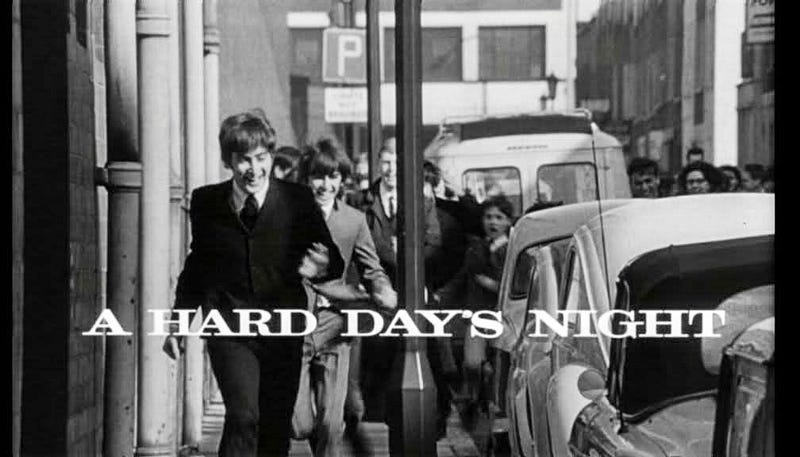

Volume Two – A Hard Day’s Night

Blame it on the tyranny of choice; which is oddly the only marketing term I recall from an Introduction to Business class in college. Combined with general malaise (either a little known military man or pandemic fatigue), I’ve been remiss in my duties and finally following through on my long promised next volume in the My Celluloid Antidepressant series.

There are far too many great options. But upon a late night stroll ruminating on my personal favorites, particularly ones that bring joy — not the Marie Kondo ‘spark joy’ variety — I remembered a particular vibrant evening — watching A Hard Day’s Night on the big screen in Santa Monica a few years back.

While we don’t have the luxury of viewing it in a packed theater at the moment, this extraordinary record of The Beatles circa 1964 brings an abundant amount of energy and joy into any proceeding.

With one caveat: If you’re not a Beatles fan, don’t bother. In fact, you’re likely a heartless, artless, and likely dead inside. I’m not being judgemental. That’s just a fact. As well as an entirely different story for an entirely different article.

Moving on.

1964 was a rough year. JFK had been assassinated the prior year, and the entire world seemed in morning. Combined with a growing “military action” in Indochina (Vietnam), people were on a desperate search for a modicum of hope in their lives. Combined with the swelling ranks of teenagers due to post-war canoodling, the stage was set for something extraordinary.

Elvis was making movies. Pat Boone was no one’s idea of cool. Enter the four boys from Liverpool. The ones weaned on American movies, teenage snarkiness (a relatively new development) and a genuine love of music. There was an alchemy present in the formation of the band, solidified by the hiring of Richard Starkey (a noted Liverpudlian drummer, with a band called Rory Storm & the Hurricanes).

Their music combined music hall, rockabilly, skiffle, show tunes, rock ’n roll and many other forms. They were an immediate splash in Europe. And they were about to conquer the U.S. as well, with a record setting appearance on The Ed Sullivan Show.

As talented as they were, no one had any idea whether the particular chemistry that resulted in an extraordinary set of songs would translate to the big screen. Walter Shenson decided to take a chance on what amounted to a lark — £200,000 sterling (approximately $500,000) on what amount to a music exploitation picture. He was able to easily pre-sell the film to a U.S. distributor, United Artist, since the deal also included the soundtrack — a guaranteed moneymaker even if the film tanked at the box office.

Shenson made two extraordinary decisions that elevated the film from cash grab to art. The first was choosing Richard Lester, the director of the Academy Award nominated short, The Running Jumping and Standing Still Film. The other was hiring an adept and skilled playwright/television writer named Alun Owen to write the screenplay. Before you give Shenson too much credit, did I mention that Running Jumping was a favorite film of all four members of The Beatles and that they were big fans of Owen’s writing?

Owen spent several days with the four members of the band and can be credited with “creating” the band members we still know and love more than five decades later.

He took one character trait from each band member that somehow still defines them today:

Paul, the cute one. John, the smart and acerbic one. George, the quiet one. Ringo, the funny (and funny looking) one.

With Owen’s ear for Liverpudlian dialogue (as well as humor) and Lester’s kitchen sink, hand-held, cinema verité approach to a day in the life of the band, the four members of The Beatles came to a life in a manner that almost matched the good luck when Paul McCartney stumbled into a music hall where John Lennon’s band, The Quarrymen, were playing.

Despite not being actors, the boys exuded bonhomie and wry charm. (And quite a lot of sarcasm.) It helped that they were surrounded by a supporting cast of very talented (and familiar faces from British television), along Tony winners and noted theatre actors. Especially Wilfred Brambell (from Steptoe & Son, remade as Sanford & Son in the U.S.) as Paul’s “very clean” grandfather and Norman Rossington, a mainstay of British comedy in the 60s (and the only actor to appear in two Beatles features as well as an Elvis film), as The Beatles’ manager.

Oh, and a uncredited cameo from a thirteen year old boy who had a bit of an impact on the music business later by the name of Phil Collins. He portrays one of the myriad screaming audience members in the theatre.

But the truth is only one thing mattered.

The music.

And, oh, the music is glorious.

“If I Fell”, “I Should Have Known Better”, “And I Love Her”, “Tell Me Why”, “Can’t Buy Me Love” and, last but certainly not least, “A Hard Day’s Night” (written quickly when they decided on the title in the last day’s of the shoot). These songs would probably elevate even the most moribund Rob Schneider movie, but instead we have the sarcasm of Lennon (snorting a Coke bottle in a successful attempt to get a drug joke past the censors), the sweetness of McCartney, the quiet intelligent of Harrison, and the goofy charm of Starr. It’s a film firing on all cylinders…

A Hard Day’s Night is often called a jukebox musical. Mainly because it shares many traits of the genre. Many songs strung together with minima plot. That much is true.

The film is so much more. It captures a moment in time in a way unparalleled by even the most compelling documentaries. It’s a cinematic masterpiece.

The title comes from a malapropism uttered by Ringo when asked how his day had gone. We should be eternally grateful for this particular abuse of the English language (versus ones we seem to experience on an hourly basis these days on social media).

Fifty six years later, we’re still on a quest to find a modicum of hope and joy in our lives.

My personal prescription for a celluloid antidepressant is to watch A Hard Day’s Night immediately. It’s an 87 minute injection of innocence, fun and the purity of what music can do to the human spirit.

To quote The Beatles themselves, a mere three years after the film’s release, “A Hard Day’s Night” is”guaranteed to raise a smile“