[alert type=alert-white ]Please consider making a tax-deductible donation now so we can keep publishing strong creative voices.[/alert]

“Gradually, the phone came to lose its terrors, but one day toward the end of October it rang, and Carlos Argentino was on the line. He was deeply disturbed, so much so that at the outset I did not recognize his voice. Sadly but angrily he stammered that the now unrestrainable Zunino and Zungri, under the pretext of enlarging their already outsized ‘salon-bar,’ were about to take over and tear down this house.”

— Jorge Borges, “The Aleph”

*

For Real, and not in vain

I sat in the L Cafe (now Bagelsmith) on Bedford Avenue, between North 7th and North 6th Streets in Northside Williamsburg, Brooklyn. Spring was coming, but the climate barely changed from winter. Southwest, past Grand Street, between the East River and the Brooklyn-Queens Expressway, la Gente ventured outside, visited each other, and murmured—not about the ‘art scene’ permeating us. The ‘white artists’ were long chismes cotidianos, well known west of Havemeyer Street north of the BQE and further west from Marcy Avenue to Division Avenue south of the BQE. These chispas against an encroaching shadow came out of spaces and borders shared between Puerto Rican, Dominican and white artists along Grand Street and Roebling Street in the Southside, along Bedford Avenue, Berry Street and Kent Avenue between North 1st Street and North 10th Street in the Northside, with more limited contacts on or around Driggs Street near McCarren Park as well as along Franklin Avenue and between Calyer Street and the Manufacturing Design Center in Greenpoint.

During the previous winter, I asked Carlos Juan Rosello, “What’s ‘gentrification’?” I overheard the word in recent conversations where we lived at 161 Roebling Street between Grand Street and Hope Street. I knew it had something to do with ‘transformation’ and ‘dread’ by how it provoked some gatherings and cast a pall over others. I was in my early twenties and homeless, breaking into and sleeping on the floor of the People’s Firehouse on Berry Street between North 7th Street and North 8th Street, when Rosello invited me to room at the duplex with Greg Wadsworth and Mitchell Valiant, who in turn hosted a revolving door of many other artists, mostly former classmates reuniting from private schools such as Rhode Island School of Design. They came for the Williamsburg ‘scene’—bohemians concentrating near the East River and living en la fabricas, of all places, to the consternation of many residents who feared for these crazy people’s health and well-being.

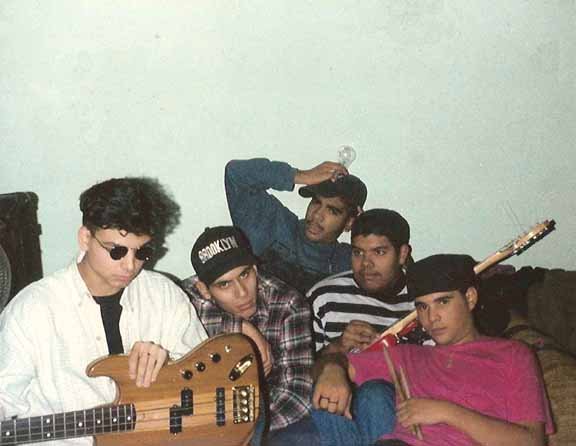

Rosello played guitar for Los Sures Puerto Rican punk rock outfit Fuzzface f/k/a Dogs of War, and opened the October Revolution. A two-day art, hardcore punk and alternative music festival ironically named after the 1917 events in Petrogad, the October Revolution transpired by Williamsburg’s East River shores where now is Bushwick Inlet Park (northeast of its soccer field,) organized by Mike Rose with others from the ABC No Rio gallery at 156 Rivington Street over the Williamsburg Bridge and across the East River in Loisaida “Lower East Side” Manhattan, including Neil Robinson, co-founder of Squat or Rot—who resided in and did business for Tribal War Records out of warehouse on India Street between Manhattan Avenue and McGuinness Boulevard in Greenpoint. Dreadlocked Dominican chaos punk Ralphy Boy from Bedford Avenue in the Southside coordinated on the River’s eastern side en Los Sures Williamsburg. Like organizers for previous warehouse events in Williamsburg, Ralphy Boy likely found lodgings in the neighborhood en los Sures and the Northside, or overnight parking, for many of October Revolution’s performers and organizers and that is a significant step in the neighborhood’s cultural and migrant history, much greater than anything achieved by civics or commerce at the time and for long thereafter—not until the 2005-rezoning under Mayor Mike Bloomberg would there be as significant a transformation in the gentrification.

The October Revolution’s nebula were more significant to the neighborhood’s cultural history than Community Board 1, the various Northside ‘activist’ non-profit community organizations that remain operating today but were established at around this time, Brooklyn Brewery’s owners, the area’s representatives from the City Council’s 33rd and 34th Districts or from the State Assembly’s 50th, 53rd and 54th Districts, even the Mayors Dinkins and Giuliani and many other parties mission-creeping from the People’s Firehouse and now decomissioned Engine 212 on Wythe Avenue in Northside Williamsburg who are usually assigned influence in the 1990s of Williamsburg’s gentrification. The reasons behind these contemporary illusory and largely egomaniacal assignments of influence, “credit,” or “power,” but truly, vanity, is because the latter groups comprise that which is “professional”—fragmenting simulacra pasted onto actual experiences and events because only then are those experiences and events tamed, made present/able and thus perceivable to the agents of gentrification, including hipsters who are as much if not more so agented. Whatever the degree of agency, ‘professional’ or ‘hip,’ all are ialdabaoth—know next to nothing about what engendered the neighborhood’s gentrification, yet scaffold a profound false consciousness, an entire economy, nay, a coherent worldview, from this professional imagination—ahistorical assumptions, not fact-based, not so much on how the neighborhood is but how it used to be, that’s brought sharply to light in advertising between Real Estate and the community’s political representatives and non-profit organizations—in conjunction, speaking volumes on the true predecessors of today’s fake news. The October Revolution and its organizers were nothing of this sort—they were alien or, in the parlance better understood to the spirit of the college campus, ‘other,’ or, at the very least, they were liminal, somewhere between ‘local’ and ‘visitor,’ were quite unprofessional, sometimes they called themselves ‘punk rockers’ and less so ‘artists,’ unlike previous waterfront and warehouse events when the Reverse was certainly True, and it is this wildness and romanticism channeled from the locals and dis/membered than re/membered by civic, political and professional parties as those just mentioned that were captured by Williamsburg’s tavern economy emergent in the Northside after gentrification’s embryonic stages in the Southside.

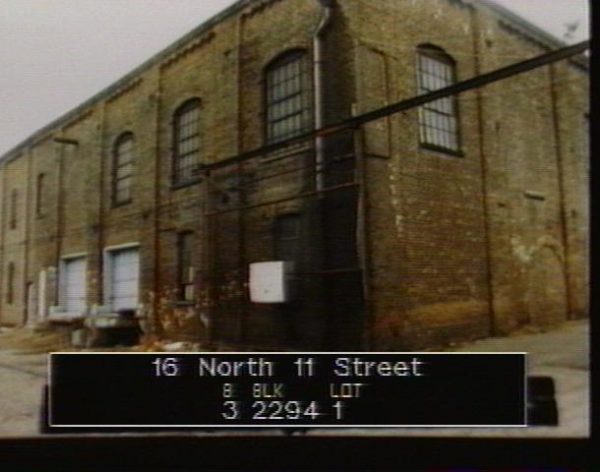

North 10th Street and Kent Avenue was ‘por el carajo,’ what we thought was el salvaje y el desierto de Williamsburg—part of a mysterious complex of warehouse buildings in varying stages of occupancy and demolition bounded north to south by North 3rd to North 12th Street and east to west by Kent Avenue and the East River shores, patrolled by multiple packs of stray dogs and humans, resided in by the most enigmatic figures, known to neighborhood taggers as the ‘Kent Avenue Piece Factories’—magnificent graffiti and street art painted and experienced there in pieces exciting and scary, wonderful and dreadful—urbanum tremendum et fascinans. The Northside is only one of three wards in Williamsburg and this particular strip of just ten or so city blocks within a single ward, zoned M3-1 by New York City for heavy manufacturing since 1961, rezoned in 2005 for the construction of luxury condominium towers, has come to define Williamsburg’s entire geography, having the further effect of homogenizing descriptions of the neighborhood not merely to any particular period but across history. It has been made to seem as if all of Williamsburg has been M3-1 all this time, a grid of abandoned warehouses with broken windows and interspersed with grassy fields and hills waiting for claim/s by white artists—more ahistorical assumptions made by vulture capitalists in the neighborhood re/presenting themselves as hipsters. Most of Williamsburg is in fact zoned R-6 for residency, certainly en los Sures and in East Williamsburg, Williamsburg’s first and third wards, respectively, as well as zoned along multiple narrow strips for mixed and commercial use—creating commercial corridors like Grand Street and Graham Avenue. By the time of the October Revolution, many of the locations destroyed in these zones in the late 1960s and early 1970s were largely reclaimed and rehabilitated by local efforts through the complex network of social service non-profit community organizations, abridged in “T/Here in Williamsburg” (Cultural Weekly, October 25, 2017). The main cultural reference by white artists in describing Williamsburg’s geography at this time has been to Andrei Tarkovsky’s Stalker (1979), produced simultaneous to The Warriors—the main cultural reference by Puerto Ricans when doing the same to Los Sures and East Williamsburg. The radically different settings for both films further suggests not only how the neighborhood’s previous zoning stretching back to 1961 shaped perception and perspectives in tension to the present but exactly where specific groups respectively trafficked in the 1990s of Williamsburg’s gentrification. The white artists remain fascinated with this Northside Williamsburg waterfront strip, and this fascination has been handed down to today’s agents of gentrification. Williamsburg’s Puerto Ricans and Dominicans have yet to understand this fixation—to their detriment.

The October Revolution brought performers from around the world, driving over the Williamsburg Bridge from Lower Manhattan, exiting and turning right on Broadway, or the Long Island Expressway either from LaGuardia or JFK airports through Greenpoint, onto Kent Avenue—other routes well traveled by locals and comprehended by white artists earlier in the neighborhood were basically unknown to the waves of people following the October Revolution, walking down Northside streets, staring at doors and peeking through windows—yearning, with an early FOMO, not knowing exactly what they were ‘missing out’ and thus provoking the locals. It was still some time before visitors seeking this ‘art scene’ would know or even think to board the L train at the Bedford Avenue station—much less use the Lorimer Street station or those that followed in Brooklyn, and forget about the JMZ elevated over Marcy Avenue and Broadway en los Sures. Navigating the neighborhood was a great mystery to visitors and not much less so to locals—the Internet was only just emerging as a commercial force and people used printed maps kept in their cars to locate the October Revolution. It would not be until the late 2000s or so that the waves that followed would walk confidently south past Bedford Avenue and Grand Street.

Joe Matunis, excellent of the North American muralistas and crucial figure at celebrated school El Puente’s recent establishment at 211 South 4th Street on the Roebling Street corner, drove Fuzzface and I helped carry equipment through the open rear truck landing of the warehouse closest to the East River on North 10th Street. The River was yards away, violent under a freezing night—the icy waves lapping against the concrete shore would not be drowned out until later, when Fuzzface turned on their equipment. I had been to established performance venues, where you entered through doors after bouncers collected admission, to go inside intact buildings with heat, water and electricity. This Piece Factory lacked electricity, shit, it lacked an interior. It was mostly demolished down to its superstructure, its joists and crossbeams exposed, massive holes yawned from floor to roof, and the ground was dotted with sinkholes. But I tell You from the Heart that nothing hung in any gallery or chancel compared to the theophany shining from every surface t/here—yearnings painted in Krylon, not Sharpie. Lumber was gathered from the complex or yanked right out of the structures, dropped into canisters all around, lit on fire and provided warmth. Gasoline generators powered the musicians’ equipment. The Fire Department showed up in the middle of all, and shut the festival down—wink, wink of course. They could have been from the People’s Firehouse, Engine 212, a block or so southeast on Wythe Avenue between North 8th and North 9th Street, Engine 216 adjoining the New York Police Department’s 90th Precinct on Union Avenue and Broadway, Engine 229 on Richardson Street between Lorimer Street and Leonard Street, or Engine 238 on Greenpoint Avenue and McGuiness Boulevard. It’s hard to recall given that Engine 212 was under constant threat by the city of declining services until its outright decommissioning finally occurred in 2003, and these ‘jurisdictions’ overlapped and were indiscrete. I confess I didn’t pay close enough attention. Someone living nearby called 911, alarmed by the gathering’s strangeness and strangers. The firemen were astonished and stared openly with eyes shining at events unfolding, at gathering, at spectacle, and confessed they didn’t want to stop anything. After issuing their warning and driving away, slowly, repeatedly braking so the men could turn and stare again and again at the encounter they were leaving behind, the ruckus resumed. We drank to Oblivion, passed out between rubble, woke on backs staring at Art, at murals, ‘throw ups,’ on the patches of ceiling above, comprehending we lay in Art as well, poems and passwords and signatures painted and scratched and burnt onto the floor, and rose dancing, drank more, continued watching the trans/figurations all around, outward the crowds, inward our hearts, with unknown but unforgettable parties. Men dressed as women. Women dressed as cosmic debris. People sported second-hand clothes and carried shopping bags from Domsey’s Thrift Warehouse on Kent Avenue yards from the East River’s Wallabout Channel, of all places. Everyone was tattooed, but semi-friendly, and always thoughtful—dramatic even in the way they begged your pardon passing by and squeezing through. We lusted and kissed and smashed and scheduled smashings in front of significant others. Punk rock and alternative music roared. Motherfuckers pulled out books and read from random pages opening. I slamdanced with Matunis in furious circles. The closest thing to my provincial mind was the Seattle grunge scene that captured MTV and mainstream consciousness, but it was nowhere near this eloquent.

Carlos explained to me that gentrification is, ultimately, about removing the Puerto Ricans from Williamsburg, and that it had something to do with the neighborhood’s white artists, some of them having organized and attended the October Revolution, perhaps. ‘Why?’ To satisfy some craven indulgences and injustices. ‘Impossible,’ I thought. My construction of white people was almost entirely informed by bochinche. My biological father is white and I was faithlessly smashing Alexandra Pawlicka from Meserole Street between Graham Avenue and Manhattan Avenue, yet I had limited contact with white people until the so-called “Warehouse Scene” that began near the East River some five or so years previous, now ending or declining with the October Revolution. The earlier Warehouse and Waterfront Events date back to 1988 and would later identify, with much and enduring bochinche, with Ebon Fisher’s Immersionism—the subject of a separate and forthcoming dedication. They were ‘artsy-fartsy,’ so to speak, while the October Revolution brought or furthered the creep, at this point in gentrification, of Lower Manhattan hardcore punk rock into Northside Williamsburg.

For the first time since childhood, since tracing then copying D’Aulaire’s Book of Greek Myths between shelves in the Division Avenue branch of the Brooklyn Public Library between Rodney Street and Marcy Avenue, I was writing without fear of being called a maricon, and getting into books and talking with other Puerto Ricans into books, such as Rosello. A fascination came over us, about Apple’s Hypercard 2.0, and some were moving towards Jorge Borges from Friedrich Nietzsche and Jean Baudrillard but always along William S. Burroughs, perhaps thus ‘Immersionism,’ but the Internet was already commercially and culturally emergent on America’s other side—the west coast, where mainstream consciousness was focused on Seattle and ‘grunge.’ A different language for interconnectedness was being created in arachnid metaphors of digitized place—the “World Wide Web,” and early search engines accessed ‘homes’ by ‘spider-crawling’ through ‘locations’ threaded by links. These white artists were unlike the white people I was reading about in Zinn, Brown and Matthieson. No way are they white liberals like in Haley’s Autobiography of Malcolm X. Still I count them among the finest people I’ve known my stormy life—comforting me during my long odyssey with homelessness. Some I dare/d love—mi yad’el.

T/here were other murmurs at this time, not by the People, not responding to but coming out of this encroaching shadow upon los Sures. I heard it so many times before out of Puerto Rican and Hispanic voices as ‘Williamsburg back in the Day,’ but now it got twisted into a radical new meaning, ‘Williamsburg before.’ ‘Back in the day’ seems like simple nostalgia about ‘how the neighborhood used to be,’ but is hyperbole and bochinche, a rhetorical device to get ass. It’s old, stretches back to World War II when Puerto Ricans began their Third Great Migration into the continental United States into places like Williamsburg, Brooklyn, but indeterminate, can mean any day—June 14, 1971, the Bushwick Riots, summer of 1984, Walpurgis 2000, 9/11, a Tuesday last March, yesterday—who knows what People will fall for. The narrator usually goes so far back in the Day as required to impress.

Williamsburg back in the Day keeps many meanings to whomever rears its head so that wherever you see at least two Puerto Ricans gathered en los Sures at least one will dispute the meaning of ‘back in the Day’ with his or her own—especially if there is a third present, competed over for affections by the other two. The men, in particular, see the use in nostalgia, to tell about their ‘endurance’ through the ‘ghetto,’ to snarl how difficult Williamsburg back in the Day seemed but how easy it all really continues to be, and well-tailor these accounts of chasings and fightings and smashings that often end in more chasings and fightings and smashings. Girls usually heard about more than told about Williamsburg back in the Day, from boys making moves, so were well aware of its suspect nature, but the telling, how one spoke without speechifying, how one kicked it, was also important, more so even, in determining if boots get knocked. The conversations overheard and taken towards this need a separate dedication that honors their poesies and poiesis.

For the first time in those few years I knew them, the agents of gentrification referred to ‘Williamsburg back in the Day,’ except in their specific context it wasn’t bravado or romance. The agents of gentrification meant ‘before them,’ and it was about terror. That is, Puerto Rican and Dominican accounts of Williamsburg back in the Day are full of scary details, but to impress. Gentrification’s accounts were of a different titillation—they meant to demonize and alienate, to talk about how all before was hell and void. We didn’t initially understand the implication, but we know it now: the agents of gentrification had come to create ex nihilo, to bring order out of chaos, forge civilization out of wilderness, and dispel or, worse, tame us feral denizens. The Southside Puerto Rican punk rockers, writers and artists would howl laughing hearing it from their mouths—how could they possibly know what was ‘back in the Day’? They just moved in! Their ‘Williamsburg before’ was unrecognizable, but we were mistaken to dismiss them, costing us an understanding we’ve yet achieved today.

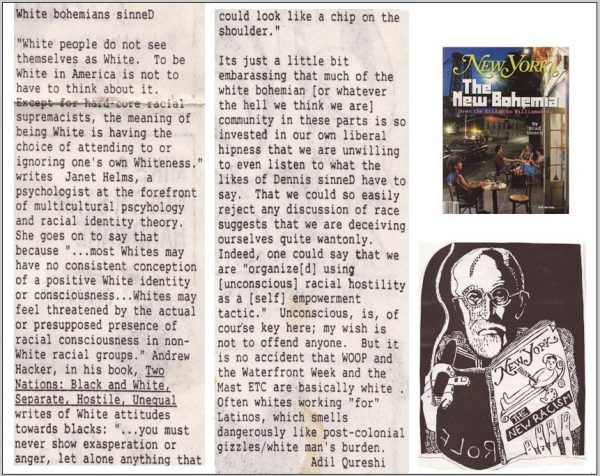

Carlos mentioned New York Magazine‘s recent feature and centerfold on Williamsburg, Brad Gooch’s “The New Bohemia” (published on my sister’s twenty-first birthday the previous summer), claiming more than two thousand artists and poets were ‘freeing thought’ in ‘solemn’ Williamsburg. Later, I was to find the New York Times had been covering Williamsburg’s gentrification for years beforehand, in similar Orwellian expressions of liberation and emancipation, but I never claimed, at the time, to read it. Gooch’s article represented an innovation—mass media attention on the neighborhood for some reason other than crime. “Two thousand artists? More like twenty thousand, dumb/asses.” We agreed this tallying was elitist and reductionist, and the disparity was peculiar, gave us pause—was it genuine? Did it have power? Was it racist, even? Still, I remained incredulous. “The neighborhood’s getting attention? Great. We’ll all smash!” Carlos shook his head and laughed.

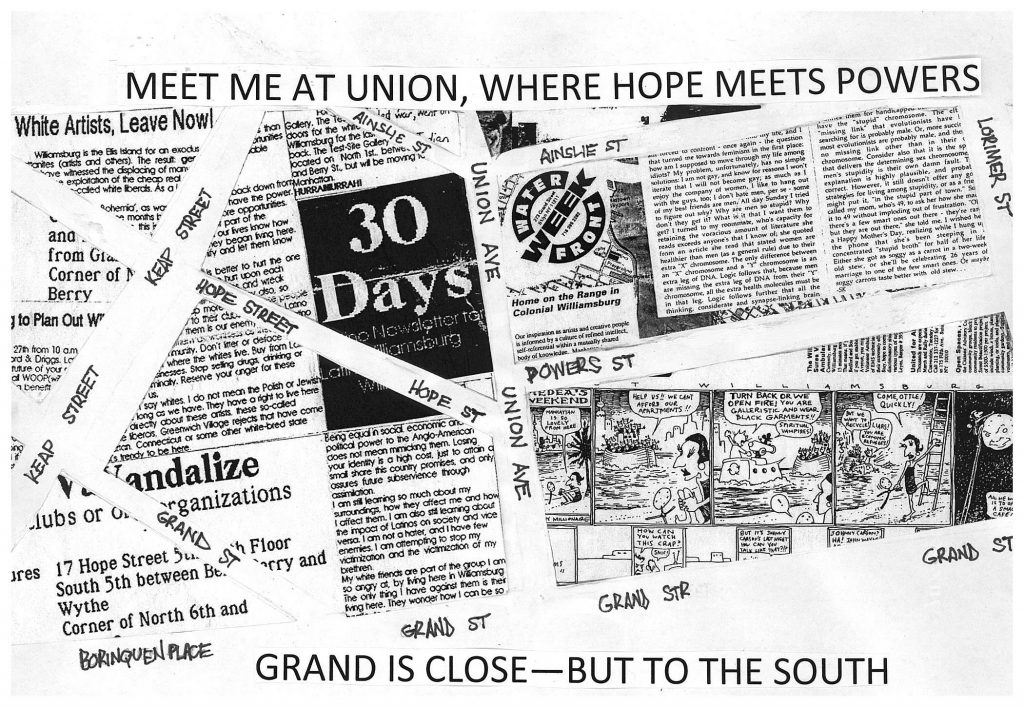

The white artists quarrelled among themselves about gentrification, they conceivably may have been doing so since 1979 when gentrification began in Williamsburg, but they never publicized their views until Chris Lanier, pbuh, and Kate Yourke, measured their peers in print. Waterfront Week “used to be a xeroxed 11-by-17 folded sheet that listed where the warehouse parties were for that particular week…It was an odd turn of co-op journalism between several unemployed writer/artist types, a ragtag rotation of ratso-level ‘responsibility’…The actual printing of the early Waterfront Week issues were done on a xerox machine donated by some hirsute activist dude campued out in the old Archive building in the West Village” (Spike Vrusho, New York Press “Waterfront Week, R.I.P.” July 16, 2002). That ‘ratso-level ragtag rotation of unemployed writer/artist types also included Kate Yourke, charismatic and humble artist, prescient writer, teacher, activist, wife and mother—truly un puente between the white artists and Williamsburg’s Puerto Ricans and Dominicans; Ethan Pettit under various pseudonyms and alter egoes, but most importantly among them Medea de Vyse—Pettit’s representation of the Androgynous Primal Man and cosmic bochinchero writing, perhaps wittingly, in Sylvere Lotringer’s style; Eva Schicker, German-Austrian immigrant and inimitable photographer, illustrator and writer, and Pettit’s wife; Genia Gould, current webmaster of www.thewgnews.com and former publisher of Breukelen Magazine; and Tony Millionaire, celebrated cartoonist and writer—Drinky Crow among his popular creations, but best was Millionaire’s ‘Someday I’ll Be a Real Girl’, his likeness of Pettit’s likeness of the megalomaniacal macranthropos writ small in Medea de Vyse, where Millionaire’s candor and visual storytelling on Williamsburg’s gentrification in the 1990s was truly brilliant. This list is abridged.

Don’t be fooled by Vrusho’s tone, which shouldn’t be mistaken for anything but admiration: in the first three years of its print, before it was sold in 1994 for $1 by Pettit to Inez Pasher and Sharron Demarrest—conservatives on North Brooklyn’s Community Board 1, and promptly “became Reader’s Digest-ed as a p.c. bastion of middle-of-the-road community boardspeak with a side of predictable animal rights pabulum” (Vrusho), the Waterfront Week eclipsed the influence of Southside publisher Autonomedia/Semiotext(e) within the white artists in general, and was, for better or worse, a bridge between Williamsburg’s locals, newer white artists and, years later, the early post-October Revolution hipsters. Outside of Autonomedia, it was the sole white artist production in this period destined for enduring influence, or at least mainstream consciousness and following, and was genuinely transformative. Like Autonomedia, it’s influence over American culture through Williamsburg’s gentrification cannot be overstated (see Cultural Weekly “T/Here in Williamsburg: Part 5: Let Me Die With the Philistines” October 11, 2017), but unlike Autonomedia, it’s history is ignored, remembered largely by its former writers and contributors—and some wish to forget, like too many things in Williamsburg.

Annie Herron’s Test Site gallery recently opened on North 1st Street between Wythe Avenue and Berry Street to crowds and increasing media awareness of North Brooklyn. Responding to the gallery’s mission, as well as misrepresentations and drooling speculation over how best to exploit New York City’s Loft Law to gain Williamsburg’s manufacturing spaces in “Big Loft Installation Style” (Waterfront Week Vol. 2 Issue 15), Lanier wrote in an untitled piece, “Can’t help feeling that I’ve seen this ‘Apartheid Test-Site’ in some other neighborhoods, and they said they were throwing the Shitthink into the sea over there, too. Southside landlords have started taking art-theory courses and are practicing writing press-releases.” In a previous issue, Lanier claimed to throw garbage out his door onto the street so his peers could ‘have some Art.’—which many, at the time, including myself, denounced as demented but secretly admired. Los Angeles had recently rioted over the not guilty verdict returned against the police officers captured on tape brutalizing Rodney King. Nathan Chukueke asked in a separate untitled piece for the same issue, “Will angry mobs have to burn art galleries before what happens in L.A. affects us all?”

The white artists were outraged and responded in Waterfront Week and 1992 is defined by a simmering all around. They also, through their own bochinche, impressed upon Kate Yourke, romantic with Lanier at the time, and she checked her peers in more measured rhetoric two issues later with “Home on the Range in Colonial Williamsburg,” (Vol. 2 Issue 17), with my emphasis, “If the arts community continues to nurture our own growth without assessing our cultural perspective we will become a tool for the displacement first of the most vulnerable and then of ourselves. If we concern ourselves solely with quality-of-life issues and environmental issues we will upscale this neighborhood while doing nothing to improve the standing of its inhabitants. Unless we work for solutions for the waterfront and the Navy Yard that are not only ecologically correct but provide low-income housing and jobs for the inhabitants of Williamsburg we will have simply laid the groundwork for the next generation of privilege while doing nothing for a community at risk.”

Two more issues later, under photograph of young candidate for Congress Nydia Velazquez, Tony Millionaire spoofed their lamentations in comic strip, “Medea’s Weekend” under “West Williamsburg Beach,” depicting Someday I’ll Be A Real Girl and Potato-on-a-Stick-Figure (Pettit and Adil Qureshi, respectively) sitting on the East River waterfront, presumably in the Northside, observing the Mayflower, packed with pilgrims, sailing over the East River to Williamsburg from Manhattan. Suddenly, a cat and mouse, Millionaire’s respective depictions of Lanier and Yourke, emerge in submarine with megaphone, shouting “Turn back or we open fire! You are galleristic and wear black garments!”

The Minor Injury Gallery in ultima thule Greenpoint was founded by celebrated Korean artist Mo Bahc and presided over by several other artists, including Kevin Pyle and Kate Yourke. Minor Injury is widely recognized as one of the earliest Williamsburg/Greenpoint galleries in the gentrification, and influential, at that time, amongst the neighborhood’s progressives. It is a crucial establishment in Williamsburg’s cultural history, organizing disparate artists—becoming one of the first organizations to connect North Brooklyn residents with New York City’s civic and cultural affairs organizations and thus the first network for serious arts funding in the gentrification. Its dissolution raised an outcry very well known among Northside residents increasingly identifying with the gentrification, and much lesser known among the Puerto Ricans and Dominicans en Los Sures where relationships were more complex, even alienated. Schicker, Pettit and Yourke disagreed over Minor Injury’s move to Manhattan from 856 Manhattan Avenue on the Box Street corner, where it promptly went insolvent. Apparently, ‘behind the scenes,’ piecing together, copying and distributing the Waterfront Week, their adversities continued.

I remained a happy dilettante over the summer and autumn of 1992. Most of my incredulity, my resistance towards believing in gentrification’s possibility, derived from macho notions that, if gentrification means to physically remove Puerto Ricans and Dominicans from their residences, somehow it involved white artists fighting and besting Puerto Ricans in the streets—comedically inconceivable. I thought of my family, the boanergeses in my mother’s generation, the fighters among the Puerto Ricans, murderers for the spirit, and scoffed at these white bohemians forcing us out. My sex life grew around the white artists, and I was enkidu. Fred Lampon, Fuzzface’s singer, would hail me from outside 161 Roebling Street as I bonded with Alex—not having a phone was one of those everyday charms of brokeassedness, and social interactions counted on mutual tenacities in locating each other. Peering out my window to answer him, I was astonished to see beat cops posted everywhere nearby. I remembered what it was like before, back in the Day for Real, when my family lived in 388 South 1st Street between Union Avenue and Hooper Street some four blocks southeast, without heat, hot water or electricity, fending for ourselves, raising gangs to protect and then hurt us under drastically reduced municipal services. Yes, the police were t/here. Apparently, they have always been here, like the wind. We felt them—we never saw them unless the worst trouble, often their own.

This was David Dinkins’ time, and soon, Rudolph Giuliani’s. We heard about Dinkins’ community policing programs, that they would cover the entire neighborhood. I joined Lampon walking the route of coverage, going from Grand Street and Roebling Street to Bedford Avenue before we had to turn right and northward onto the Northside, finishing at North 7th Street—the L train station. The police were concentrated on this route with at least two beat cops to each block, at least one at each intersection. We found no beat cops elsewhere across the Southside as we continued our day. I’d repeat the trip with others. We wouldn’t find any beat cops anywhere else but those routes—for years.

It was natural, then, to associate ‘gentrification’ with the police parallel to how it is associated with crime and criminology for the agents of gentrification. And talk followed, whimsical, about ‘what it takes to resist and overcome gentrification.’ Together, we’d blurt out the usual slogans: it would take a revolution, and like Malcolm X taught us, revolutions are violent. We would need guns and heads to run deep, but trim enough to implement guerilla strategies in street riots. Things would get damaged. People would get hurt. And we were ass broke, but more so, we were heart broke. Too human/ist for that kind of war, or already shellshocked. Maybe sedated. Maybe enkidu. The Puerto Rican punks just wanted to play punk rock—and I, unusually, started to wonder. Quietly to myself, I connected—if the October Revolutionaries had anything, even the slightest, to do with ‘gentrification,’ whatever that was, to resist gentrification would need an iconoclasm, and not the fake kind where attention isn’t extinguished but is merely transferred between artists, but an aniconism, to oppose Art and artists intrinsically, to never enter the galleries, cafes or bars—unless invited and always infiltrating, to sleep with eye/s open and never completely a night, to be haunted and haunting, a stranger even to Y/our People.

This is crazy. Why would I consider such things? I resisted those feelings, ‘Why should I look past my needs and wants?’ I was having such a good time, going to galleries and events and never looking at the artwork—just like everyone else. Not yet twenty-one but already some years homeless, I found not roof but roofs for shelter, was finally warm and slept in a circuit of bedrooms speaking, falsely, without humility, about ‘Art.’ A girlfriend of one of the many white artists in and out 161 Roebling’s door lived in a storefront on Grand Street between Roebling Street and Driggs Avenue, and kept Ayn Rand next to Howard Zinn on her shelves. She noticed my writing and increased interest in books and recommended Atlas Shrugged along with The People’s History of the United States. For all my life, passing before many Williamsburg bookshelves experiencing so many different collections, and seeing this coupling repeated, I have never understood this shelving peculiar to the libraries of Williamsburg’s gentrification.

I had to save money to munch at the L Cafe, so went t/here to hook up, carrying works by Goethe, Baudelaire, Nietzsche and Kierkegaard I borrowed from the artists and pretended to read—I barely cared to open. This time, I bore my nose into Atlas Shrugged, ignoring everyone around me over multiple readings, struggling against the feelings Rand usually elicits. I couldn’t eat the whole grain bagel with peanut butter, banana and honey that I ordered on that visit when I finished the final page. In a flash, I knew I would never return. I finally understood gentrification’s meaning. Past my selfishness and my gratifications, I saw the end of the Puerto Ricans—not just in Williamsburg, but everywhere.

An/other voice came right after, familiar—usually bothering me on Sundays on my way to Transfiguration Church on Marcy Avenue and Hooper Street or, later, at St. Mary’s of the Immaculate Conception on Maujer Street and Leonard Street, but always silenced once walking through the doors and entering the nave—of the Blocker, repeating me: ‘you’ll have insomnia, feel pursued, never be satisfied, nor enter a cafe or gallery or school as anything but an infiltrator. You’ll alienate your great love/s and be a stranger to your family and Y/our People’—ha! I joked, bittersweet, that one will be easy. D’Aulaire’s Book of Greek Myths appeared in my hands hovering over Atlas Shrugged. The design and format of those early paperback editions wasn’t so different than the tabloid sides of the Waterfront Week stacked on a windowsill nearby. I left, grabbing a copy of Waterfront Week, but don’t recall what issue or what it featured. I couldn’t. Rolling it into a rod and antennae, I carried it over my head on the way back to 161 Roebling, to capture lightning.

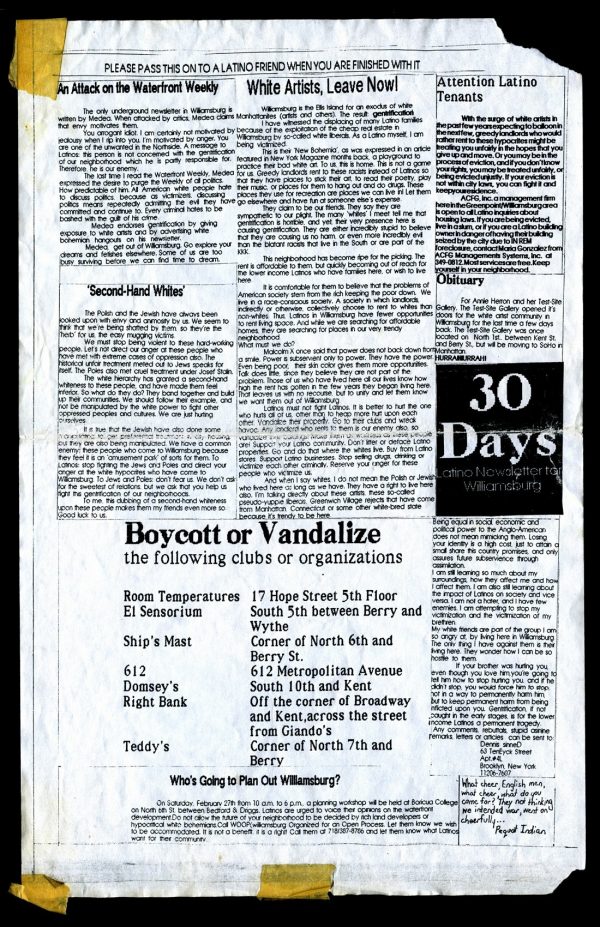

Rosello wasn’t home when I wrote all the words, printing in different typefaces, cutting columns out of documents with margins measured to paste alongside each other on that first issue of 30 Days—tabloid, to match the white artists’ Waterfront Week. He would write for later issues and edited the third, when it started to look more like something D’Aulaire would illustrate if one day he woke up against illustration—aniconic, anarchist and antinomian. I made the rounds and borrowed enough money to make 100 or so copies, and pasted copies onto artist and commercial establishments, including the doors of several white artist residences. It called for violence, riots, polemics, vandalism and boycotts against Room Temperatures, El Sensorium, Ship’s Mast, Cafe 612, Domsey’s Thrift, Right Bank, Teddy’s—anything within means to fight gentrification. It gained the attention of City Hall and the New York Police Department. I attacked Waterfront Week, Kate Yourke and the Test Site gallery, and like a true penitent-dilettante spelled it Waterfront Weekly. For months, writings on gentrification were exchanged in public by numerous residents—largely Puerto Rican and Dominican writers and artists en los Sures writing for 30 Days and white artists in the Northside for Waterfront Week. Later, Yourke and I were fam, like many of the participants in the flame war.

A part of me thought nothing would come of it. Why would anyone care? But the flame war lasted until six issues of 30 Days were published into the 1993 summer, resumed in 1994 with another volume of 30 Days a/k/a Pachakuti, again in 2009 when Facebook reunited, of sorts, North Brooklyn’s white artists and rhetoric between them about ‘Williamsburg before’ remained unchanged and provocative, and spilled onto public comments threads in numerous blogs and websites, notably that of Gothamist and L/Brooklyn Magazines or orwellian “New Brooklyn Media” (now largely and already defunct). The flame war updated in 2016 with a new flank of Puerto Rican and Dominican residents, around controversies over the Fuchs gallery and white artist vandalism of Will Giron’s home in Bushwick (Emma Whitford, Gothamist “Bushwick Gentrification Flame War: ‘This is the Face of Hipster Racism.’” (January 7, 2016)). Skirmishes continue t/here, and Pettit has dropped much pretense and gone full alt-Right. The flame war is now cool, but waits fire—is not yet forgotten.

*

To J, K and Ari/el,

all are agents, but some are Infiltrators.

How then We see in this House of Shining Mirrors?

A spark of darkness makes shadows of light

October Revolution would be followed, in the years thereafter at around the same location in what neighborhood taggers recognized as the Kent Avenue Piece Factories, by Radioactive Bodega and the Beer Olympics, and represented the final Waterfront Events, beginning in the mid-1980s, that brought mainstream consciousness to Williamsburg. Also transpiring, but somewhat separate from Radioactive Bodega and completely apart from the Beer Olympics was the Mustard event on an entire city block, covering all parcels, between Wythe Avenue and Kent Avenue from west to east and between Metropolitan Avenue and North 1st from north to south. The Beer Olympics preceded the tavern economy often mistaken for ‘creative economy’ that is robustly enjoyed by Northside Williamsburg and Greenpoint in the present.

Pettit is proprietor of the Pettit Gallery in Park Slope. Schicker hosts illustration classes and groups there.

Rosello teaches at the El Puente Academy for Peace and Justice, and is the subject of a forthcoming quasi-biography on Williamsburg 1982-1995, No/w/here Northside.

Kate Yourke is fam and we still talk about the gentrification nearly every chance I impose upon her.