An ambitious exhibition of African-American art from the 1960s and 1970s, now on view in San Francisco, shines a fresh light on the powerful work that grew out of the turmoil of the period.

The social influences are familiar: the Vietnam War, the civil rights and black power movements, the assassinations (two Kennedys, Martin Luther King Jr., Malcolm X), the Watts riots, the rise of the Black Panthers in Oakland. Soul music, with Aretha Franklin demanding respect, entered the mainstream.

Organized by the Tate Modern in London and now at the de Young Museum, “Soul of a Nation: Art in the Age of Black Power 1963-1983” features more than 150 works, including paintings, sculptures, photographs, assemblage, and graphic art. The sprawling show presents styles ranging from Pop realism to abstraction; some of the works were created as tools of political protest, others as art for art’s sake.

Benny Andrews’ striking Did the Bear Sit Under a Tree? of 1969 (top image) combines both impulses. On the right side is an anguished-looking man who raises both of his fists, one perhaps in a black power salute, the other seemingly to prepare for a fight. On the left is a partial image of the American flag. The paint is applied in an expressionistic style, so thickly around the man’s face that his nose extends from the picture plane like a piece of sculpture. The meaning of the work is far from clear. Is the man attacking the flag? Defending it?

By contrast, photographer Roy DeCarava’s Mississippi Freedom Marcher, Washington, D.C. of 1963 is simplicity itself. The tightly framed black-and-white picture focuses on the face of a serious young woman in a protest march against Southern racism. She’s a model of controlled anger and determination, and it’s an image that sticks in your mind.

Barbara Jones-Hogu’s Unite of 1971 also depicts protest marchers, though her graphic style is completely different from the DeCarava portrait. She arrays a monochromatic line of protesters, fists raised, across the lower half of the picture. In the background above is a visual explosion of red, blue, and yellow banners, all proclaiming the slogan “Unite.” It’s like an African-American take on the revolutionary imagery of 1920s avant-garde Russians.

The sculptures in the show cover the spectrum, from carefully carved and polished wood to found objects turned into art. Betye Saar’s Sambo’s Banjo of 1971-72, for example, features a doll dressed like a minstrel player hanging by the neck inside a banjo case lined with a cheerful red and yellow fabric. The black case also contains images of a lynching and a rifle, as well as a small black skeleton with a noose around its neck. Nearby is a sculptural slice of watermelon. The combination takes away your breath.

Another powerful sculpture in the show is Melvin Edwards’ Curtain (for William and Peter) of 1969. The curtain, about 24 feet wide and 12 feet tall, is formed from dozens of strings of barbed wire hanging from a rod and held down by a long drooping line of galvanized chain. When lit from the side, as it is in the de Young’s excellent installation, the work casts a shadow on the wall behind the curtain, creating a visual echo of the curtain. It’s creepy and elegant at the same time.

Not all of the works in the show focus on the past (and present) oppression of black Americans. Instead they offer upbeat, even heroic takes on portraiture. Phillip Lindsay Mason’s The Hero of about 1979, for example, presents a young black man as a cartoon superhero leaping forward from a bright red and yellow explosion. He would feel perfectly at home in a Roy Lichtenstein painting.

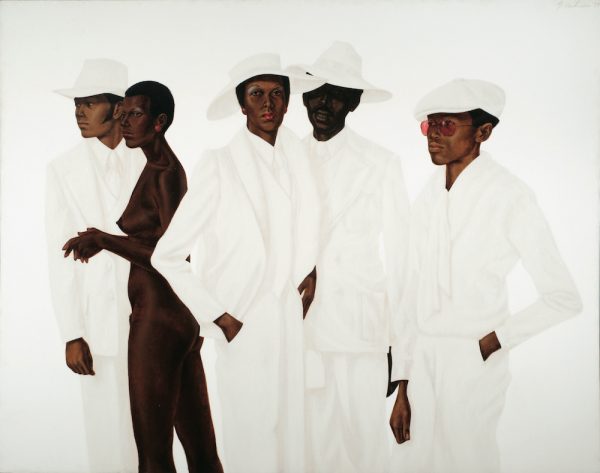

Barkley L. Hendricks’ striking group portrait, What’s Going On of 1974, offers a more serious and elegant approach. In the life-size, almost 7-foot-wide painting, he arranges five young people. Three men and one woman are dressed in stylish white suits and hats, while one woman is, incongruously, completely nude. Three of them look off to the left; the central pair coolly address the viewer. The title of the work, of course, is taken from Marvin Gaye’s 1971 hit Motown song, and perhaps the lyrics offer a hint at the meaning of the work:

Mother, mother

There’s too many of you crying

Brother, brother, brother

There’s far too many of you dying

You know we’ve got to find a way

To bring some loving here today, yeah.

“Soul of a Nation: Art in the Age of Black Power 1963-1983” runs through March 8, 2020, at the de Young Museum, Golden Gate Park, San Francisco. It will be on view at the Museum of Fine Arts Houston from April 26 to July 19, 2020. An extensive catalog is published by Distributed Art Publishers Inc.

Top image: Benny Andrews, Did the Bear Sit Under a Tree?, 1969, oil on canvas with painted fabric collage and zipper, © Estate of Benny Andrews/licensed by VAGA at Artists Rights Society, New York, courtesy Michael Rosenfeld Gallery, New York. All images courtesy of the Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco.