Jordan Casteel has been called a rising star in American art, and it’s clear why from a visit to her first solo museum show, which just opened at Stanford University after its debut in Denver.

“Jordan Casteel: Returning the Gaze” features 29 large paintings made in the past five years, almost all of them portraits of her African-American friends, schoolmates, and neighbors. They’re energetic and intensely colored, usually serious and highly focused, occasionally sweet and sentimental.

The show begins with a knockout series of nude young men painted in 2014 as her master’s project at the Yale School of Art. (All the subjects were recruited from the Yale School of Drama, almost all of them actors.)

In Galen 2 (above), for example, a thoughtful young man sits sideways to the viewer in a metal-and-plastic chair in his kitchen, left elbow on knee, hand raised to his chin, eyes focused directly on the viewer. There’s a kettle on the stove to the right, a black-and-white checkerboard floor, a radiator in the background. All seems relatively normal except Galen himself, who is rendered in an otherworldly green that complements the pale green of the back wall.

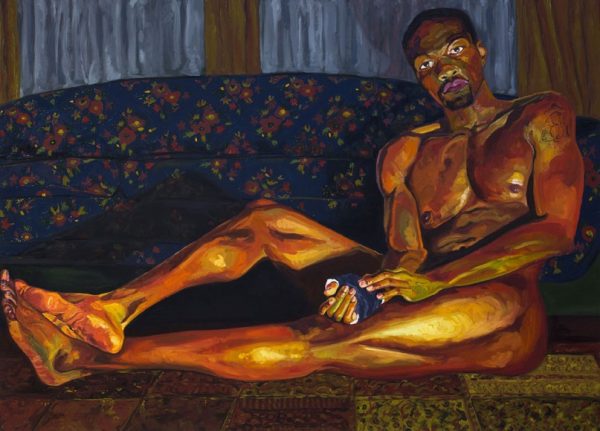

Others in the series are also oddly colored, such as the pale blue-green subject of Jireh, who contrasts with the yellow, orange, and dark blue of his sofa. Even in the more chromatically accurate portrait Yahya, the tones in the subject’s skin range from dark brown to tan, with bright orange and white highlights and dark greenish shadows. The muscular, bearded man reclines on a blue flower-print couch and shows the kind of coiled power that demands your attention.

Yahya is also a modern reversal of a very old artistic genre, the reclining female nude, which goes back at least to Giorgione and Titian and forward to the Impressionists. Manet’s unsmiling Olympia of 1863, dressed only in a black ribbon around her neck, stares back at the viewer with the same focus and intensity as Yahya.

Casteel moved to Harlem after finishing graduate school, and many of the later portraits in the show feature her friends from the neighborhood. (There are also a handful of tightly cropped views of subway riders’ torsos, their hands holding mobile phones or shopping bags.)

In Benyam of 2018, an older woman with a deeply lined face and a slight smile, wearing a white shirt and a black apron, sits in front of a cafe bar. Next to her are two younger men, both in black shirts, one wearing a baby-blue baseball cap and the other a gray fedora. The background includes a sketchily rendered line of wine glasses on a shelf and a wall of pictures.

Is the woman the owner of the cafe? We don’t know. Like the portraits of the nude men, the trio stare straight back at the viewer, as if to say “We’re here.”

With this remarkable show, Casteel, now 30, seems to be saying the same thing.

“Jordan Casteel: Returning the Gaze” runs through February 2, 2020, at the Cantor Art Center of Stanford University. A catalog is published by the Denver Art Museum, where the show was organized and ran from February through May.

(Top image: Jordan Casteel, Galen 2, 2014; oil on canvas; collection of Charles L. Casteel; © Jordan Casteel; image courtesy of Sargent’s Daughters, New York.)

Noguchi-Hasegawa: A Midcentury Modern Friendship

The Japanese-American sculptor Isamu Noguchi and the Japanese painter, calligrapher, writer, and polymath Saburo Hasegawa are the subject of a handsome exhibition focusing on their work and friendship during a five-year period in the early 1950s.

The show, which just opened at the Asian Art Museum of San Francisco, features more than 100 works, including Noguchi sculptures in wood, metal, and stone, as well as his iconic Akari paper-and-bamboo lamps. Hasegawa is represented by paintings and drawings on paper, experimental photographs, block prints, and rubbings.

The two men met in Japan in 1950 after pursuing similar career paths. Both had traveled and worked in Europe in the 1930s. Hasegawa, born in Japan, met Piet Mondrian in Paris and also visited the U.S. before returning home prior to World War II. Noguchi, born in Los Angeles to a Japanese father and American mother, worked at the Paris studio of Constantin Brancusi. He also voluntarily lived in a U.S. internment camp in Arizona for several months in the 1940s.

When Noguchi visited Japan in 1950, Hasegawa became his guide, translator, and friend as the pair explored Japanese art at a time of rapid modernization. Noguchi went on to a long and prominent career as a sculptor before his death in 1988 at the age of 84. Hasegawa died in 1957 in San Francisco at age 50.

While Noguchi’s sculptures typically convey solidity and permanence, as in the installation view above, much of Hasegawa’s art seems almost offhand, like doodles or improvisations on traditional Japanese calligraphy.

In From Lao-tzu of 1954, an ink drawing on a tall sheet of paper that recalls a Japanese scroll, Hasegawa arranges cartoonish sketches of a house, a decorated vase, and an ambiguous circle emitting thick lines — a rimless wheel? a sun with rays? — in the upper half. The lower half is filled with small calligraphy that looks like a flock of birds or butterflies. While there’s a cheerful, childlike feeling to the work, it also seems more and more sophisticated the longer you look at it.

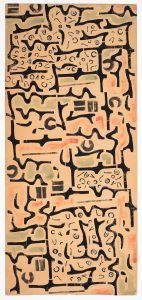

Hasegawa’s Great Chorus of 1952 is a more finished work, a labyrinth of black ink shapes on another tall sheet of paper that’s been tinted in shades of tan, green and orange. It’s completely abstract, and difficult to see any “meaning” in the work, but it has a graphic energy that’s hard to resist.

Hasegawa loved to play with textures: the contrast between smooth black ink applied to rough brown burlap, or the wood grain that shows in block prints. Noguchi’s surfaces, on the other hand, are typically smooth, or highly polished metal or stone or wood that contrasts with the unfinished material.

What brings the two artists’ work together is their exploration and fusion of modernism and traditional Japanese art.

“Changing and Unchanging Things: Noguchi and Hasegawa in Postwar Japan” runs through December 8 at the Asian Art Museum, 200 Larkin Street, San Francisco. The exhibition was organized by the Isamu Noguchi Foundation and Garden Museum in New York and was on view there and at the Yokohama Museum of Art earlier this year. An extensive bilingual catalog is published by the University of California Press.