AMY is a haunting tribute to the Lady Day of our day and her irresistible siren song. Winehouse was pure, ineffable talent in the raw. The beehive, the Cleopatra liner, the tattoos, this raspy voice that spewed truth serum lyrics right from her core. This bright flame that shot up like a star, only to burn out so quickly. Her talent and her tragedy recall the likes of so many fallen greats; you have the impression of watching a young Billie Holiday or Judy Garland at play in this intimate documentary portrait from director Asif Kapadia.

That filmmaker Kapadia shares Winehouse’s trademark North London accent seems to have provided him a key to unlocking the hearts and tongues of those closest to Amy Winehouse. Kapadia becomes confessor to her innermost circle in reconstructing a portrait of the real Amy they knew and loved. They reveal a cheeky, perceptive, piercingly honest young woman, in relief to the performance persona of her construction, and in sharp contrast to the relentlessly cutting and critical gaze of the mass media.

Early on in her career, Amy defines success as “the freedom to work with whoever I want and to go to the studio whenever I want.” Ironically, the last recording she ever made was a duet rendition of “Body and Soul” with her personal idol, Tony Bennett. The footage from that session that is included in the documentary is priceless. Bennett’s deep respect for her talent is palpable. In Bennett’s words, Amy Winehouse is “someone who sings the right way.” His patient and gentle guidance is deeply moving, as he provides a harbor of sane shelter, albeit temporary, to the floundering young starlet, adrift on the high seas of callous, indifferent treatment to which she had become accustomed.

When challenged by Amy’s friends about her drug use, manager Raye Cosbert reputedly encouraged them to back off: “Girls, there are a lot of sorts of professionals — lawyers, doctors — who function on this stuff,” he derides them. So many of those upon whom Amy most depended tried to sweep her addictions under the carpet. “It wasn’t a shock,” echoes her childhood friend, “You could see she was going down a certain path.” While those who loved her were unable to save her, they have managed to pay homage to Amy and her many accomplishments in this beautiful documentary.

If Amy Winehouse’s signature sound has ever haunted your dreams, you will appreciate the opportunity to spend a couple of hours in her presence in the dark, memorializing her memory, marveling at the formidable talent before you, celebrating all that Amy Winehouse was, and mourning all she might have become.

“The dream I have is that the film will help change how we treat people,” Kapadia confesses. Meanwhile, we watch, sidelined with distress, as we witness Lindsay Lohan wrestle similar demons to the death. I privately lament.

I value the opportunity that I had to talk with the perceptive and talented director of Senna and AMY, Asif Kapadia, at the Ritz Carlton San Francisco Hotel, where he shared valuable insights about the Amy Winehouse he discovered and his unique approach to crafting such an immersive and loving tribute.

Sophia Stein: You open the film with this home movie footage of Amy Winehouse at fourteen singing “Happy Birthday,” and it immediately conjures up an association to Marilyn Monroe. We feel as though we are treading hallowed ground, witnessing such a raw, natural talent. How did you come across that footage?

Asif Kapadia: It’s a word that comes up a lot — rawness. I think that is one word to sum up Amy Winehouse and maybe the film. There is something about her; she just has something. No one had tried to mold her into a triangle.

That footage came from Lauren [Gilbert], Amy’s childhood friend, who is holding the camera. They grew up together; they’re like sisters. Lauren took a long time to have the trust and the confidence to speak to us, but when she did, she had all this lovely stuff like that “Happy Birthday” footage. — And the tape of when they were on holiday together in Mallorca, where Amy is doing the funny voices. You can see how close they were in that footage.

Sophia: David Joseph, Chairman and CEO of Universal Music UK, approached producer James Gay-Rees (Senna, Exit Through the Gift Shop) about making this film in order “to set the record straight,” “to tell the proper story of Amy Winehouse.” What impressions specifically did you set out to correct?

Asif: To be honest, at the beginning, I really did not know that much about Amy’s story. I am quite into — getting into film projects where I know nothing about the story. In other words, you work it out as you go along. That journey is part of the fun.

I live in North London, very close to where Amy Winehouse lived. I never really understood why her life turned out the way it did. I never really understood why she was performing when she was in such a bad way.

So I had a lot of questions about her latter period, and I didn’t know anything about the early period. I had never met her. I had never seen her perform live. So it wasn’t like I had a direct connection to her.

I had done this film Senna — which is about a sports person, and I didn’t want to do another sports film. This was a film about a musician. And it was a film about the city I love, that I was born in, that I live in: London — because Amy is somehow very much linked to London. It felt like it was a story about our times. It felt like it had happened just yesterday and that somebody needed to talk about it. A fiction film can take years to get made, and by the time it gets made, it’s out of date. I wanted this film to be relevant to now … because everyone kind of remembers what went on and nobody really understood who she was, or why it happened, or how it happened.

Sophia: I was so struck by the dichotomy in your film of Amy — this nice, cheeky, young Jewish girl from the North of London, in contrast to this persona that she had constructed for herself as a singer.

Asif: Or persona which was given to her. She had created a persona, and then she became a persona beyond her control. The media had decided, this is who you are. In the U.S., she was a train wreck. In England, she was this tabloid girl. That is so not who she really was, but that’s what she became. Even if you don’t read the tabloids, you got your opinion of Amy from the tabloids. Somehow it seeped into your skin, and that’s what you thought of Amy Winehouse. People didn’t talk about her being clever. They didn’t talk about her being intelligent and funny, beautiful, a guitar player … they didn’t know she wrote the songs. All of that great stuff got left behind. All they saw was someone stumbling around drunk all the time.

Sophia: A lot of people think that Amy died of a drug overdose — in point of fact, she died of alcohol poisoning –

Asif: It’s still a drug overdose. If you’re an addict, it doesn’t matter what it is: it could be heroin, it could be crack. Alcohol is freely available. Alcohol is actually the biggest problem, the biggest drug. It’s not better that she died of alcohol than crack. She died at twenty-seven because she had an addiction problem that was never dealt with.

Sophia: I felt like your movie showed me how Amy died because she was so extremely vulnerable, she had great difficulty weathering the vicissitudes of life. At one point in the film, Amy tells her manager: “Love is in some ways killing me, Raye, Raye.”

Asif: She died because her heart stopped … but her heart stopped because of bulimia and all the alcohol over the years. But yes, her life became a very lonely life …

The whole story really is about love: parental love, love relationships, love between best friends. It’s about broken hearts. It’s about creating something positive out of something negative. Writing songs as diaries because you’re in pain. It’s about the real love – which is dark and painful. Amy self medicated; her life was basically a life of taking things in order to not feel pain. In the end, that’s what killed her.

Sophia: There are many things that impacted Amy deeply — the break-up with her boyfriend, the death of her grandmother. You said that one of the reasons that you wanted to make the film was to try to understand “How can someone die like that in this day and age?” What do you think could have been done to help her?

Asif: Her friends all felt like there was an opportunity early on, before she became famous, to help Amy. They could all see that she had radically changed in a very short space of time around the time she met Blake [Fielder; the drug addict whom she would later marry]. Amy herself told them that she was in trouble and that she wanted help. She needed certain older people with positions of responsibility in her family to say that they wanted to help her. For whatever reason, at that point, those people did not help her. At that point, they weren’t sure that addiction was an issue. Her friends told me that they felt that this was a missed opportunity.

Later on, the machine — the fame and the media — took over. She became a rock star. She became famous around the world.

Her most famous song was the one that killed her — “REHAB.” Suddenly, how can Amy Winehouse — a very proud young woman — go against what she’s been singing and check herself into rehab? It felt as if, the bigger she became, the more impossible it became for her to get the help she needed.

Sophia: Amy’s mother, Janis, describes how at fifteen, Amy confessed that she was bulimic. Her mother did not do anything about it. “My feeling was, it would pass,” Janis explains.

Asif: The mother, you know, she’s a good woman. She’s sweet, Janis. As she says, she wasn’t tough enough. Amy was a very strong personality, and her mother wasn’t very well during that period. Janis had multiple sclerosis, and I think that she just couldn’t cope, really, with the situation. I don’t think Janis has a bad bone in her body, but she wasn’t tough enough for Amy. … And there was another person in the family who had such a big personality which made the dynamic even worse.

Sophia: On Amy’s left shoulder are tattooed the words: “Daddy’s Girl.” Can you talk about Amy’s relationship with her father?

Asif: She obviously loved him, and he loved her, but there was an issue that happened when she was very young. He met somebody else, and he went off. [He left the family.] Kids just want their parents. They want the parent who’s not there. I think Amy just wanted her dad. Later on, when he was around, he was a person that she really wanted to listen to. They all became so confused with fame and money — the music was doing so well. I think maybe sometimes she just wanted him to be “the dad” and not to be part of the management team.

The person who was the strongest matriarchal figure in her life was Amy’s grandmother, Cynthia. Amy has another tattoo on her arm for her grandmother. Cynthia was the person who said, “No!” Who laid down the law. She’s the one who kept both Amy and Amy’s father, Mitch, under control. Nick [Shymansky, Amy’s first manager] very perceptively remarked that Cynthia dying somehow profoundly affected the two of them. When Amy’s fame became so huge, both of them got a little bit out of control.

Sophia: You decided to structure Amy’s story like a Bollywood film –

Asif: With classic, Indian musicals, the songs get released first; people know the songs, and then the film comes out. Here, we had the songs, but we didn’t know what the story was. For me, it felt natural to build this film around these songs which are all narrative. Each song has a story. Each song adds something to Amy’s character and her personality, and moves the story forward. I realized quite early on that the lyrics were going to be key. Songs are part of the story in Bollywood films. First and foremost, AMY is my version of a musical.

Sophia: What were some of the mysteries that you had to unravel when you were looking at those lyrics?

Asif: One of Amy’s most famous first songs is: “What Is It About Men.” Another song is called “Best Friends,” which is about Juliette. Another song, “Stronger Than Me,” talks about what she is searching for: a man who is stronger than she is, who is going to be there for her. Then later on, she writes “Rehab,” which is based on a real incident. “You Know I’m No Good” is about self-esteem. “Love Is a Losing Game” could almost sum up Amy’s whole life! All of these songs are already there; we know them. We just didn’t realize how [confessional they were]. When you read the lyrics, you realize how important each song was at a particular moment in time. Each song represented a feeling that Amy had, like reading a page from her diary. In this way, the film almost becomes her diary. It’s very personal at times. Very intimate.

Sophia: Yes, that is how it felt to me. It felt so intimate.

Asif: You’re in there with her, the whole way through.

Sophia: You see her face almost in every shot. We never leave her. We are spellbound by her presence. Winehouse’s closest friends had taken a vow of silence not to talk about their friend after her death. How did you penetrate those walls?

Asif: I just spent a lot of time getting to know them. Not being too pushy, just talking to them, and trying to make them to understand where I was coming from. I wanted to really do what was important to them, to reveal the real Amy, not to rehash the public perception from that time.

And I was not in a rush, you know. I spent a long time making this film. Senna took five years; AMY took three years. So I said, “Listen, whenever you’re ready, I’m here.” And bit by bit, word would spread. The people I was interviewing would all talk to one another and say, “You should meet him. Actually, it’s probably worth doing.” For each person I met, it became a bit of a therapy session. They would let a lot of stuff off their chests, talk about things that they had never really talked about with anyone else. And they felt better for it. I could see by looking at them after we had spoken that they felt better for having spoken about it. Then they would tell another friend, “Look, maybe you should talk to him.” And it just spread. In the end, I spoke to over one hundred people.

Sophia: What do you use to record the interviews? Do you use a video camera?

Asif: I don’t film the interviews. I found a really good recording studio in Soho, in London, which was very easy to access. Literally, there’d be a room with a microphone on a desk, and just the two of us in the room. A mixer in the other room, so nobody was with us in the space. The lighting was very harsh, so I said, “Turn the lights off.” We would pretty much sit in the dark and just talk, for however long I had. If I had twenty minutes, an hour, two hours … Nick and I would be talking and then we’d look at our watch and realize that we’d been talking for five hours. You know, it became this process of just getting everything out. Everyone had a story to tell. It was about cross-referencing what everyone was saying in order to piece together Amy’s life to create this kind of mosaic.

Once they had spoken to me, each person would feel confident, happy, trusting enough to offer, “I’ve got some photographs,” “these home videos,” “this answer phone message,” whatever it might be. So the visual side came together after the audio interviews.

Sophia: Producer James Gay-Rees, editor Chris King, and you all worked together on Senna – you make for quite a powerful filmmaking trio. How did you come together?

Asif: And the researchers. There is also this sound team. There are about ten of us actually involved in the process. We take this very, very rough archive footage and make it into movies. A lot of that is the picture side, with editor Chris King, but I have a great sound team who also elevate the material. You have this home video which suddenly you’re hearing in the cinema, and it sounds amazing. I’ve worked with many of them for years. We made student films together [at The Royal College of Art]. It’s like a little family. There are about twelve of us that come together every few years and make a movie. It’s really fun. There’s no B.S. It’s just a really good group of creative people who care about what they do.

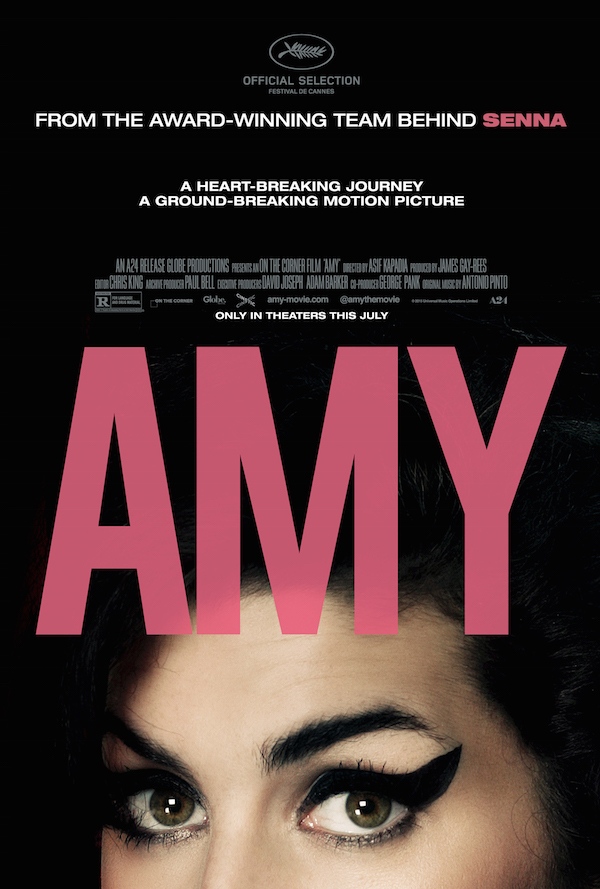

“AMY,” directed by Asif Kapadia, photo courtesy of A24 FILMS.

Sophia: If you were able to resurrect Amy from the dead, what would you ask her? What would you tell her?

Asif: There are a couple of things that I would say. At one point, I would have encouraged her to just knock out any old music — something experimental. To get rid of the pressure of following up this huge mega-album, Back to Black — an experimental hip-hop album. Or do a jazz album. Have a failure; failure is great for a long career. Everyone screws up at some point. I think that it was a difficult thing for her to keep having to do better than the last one.

I’m also a big advocate of travel; I love traveling. I think you understand the world much better and you understand your own part of the world, if you go and see more of the world. I wish that Amy had traveled to India. I wish she’d have gotten away from Camden. I wish she had just realized that the world doesn’t revolve around her, there is so much more going on. Maybe that would have helped her to realize a way out of her depression, her heaviness. Maybe she would have realized that there are people who have more, there are people who have less, but there’s so much more to enjoy and to experience. Maybe she would have gone off in a totally different direction — like the Beatles did — if she had gotten the chance to experience something else.

From such a young age, Amy had music. Once she fell out of love with music, once the music became a problem, she didn’t have anything else. I think that’s never healthy. You’ve got to have more than one thing in your life.

Top Image: Amy Winehouse, “AMY,” directed by Asif Kapadia, photo courtesy of A24 Films.