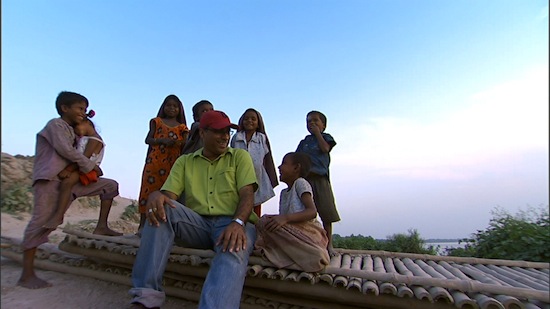

The Revolutionary Optimists profiles the lives of four young agents-of-change: Salim, Sikha, Kajal, and Priyanka, who — living in the poorest of neighborhoods in Kolkata, West Bengal, India — are working to better their communities and lives. Under the mentorship of Amlan Ganguly, through the NGO that he founded, so aptly named Prayasam (“Their Own Endeavors”), Amlan inspires his mentees to dream big and challenge the notion that marginalization is written into their destiny.

The son of a diplomat, Amlan himself was raised in a palace. Early on, he quit the “purely mercenary” profession of the law, which he discovered was contrary to his nature, to work towards fulfilling a dream articulated by Dr. Martin Luther King: “the eradication of poverty in the land of plenty.” Amlan approached adults in the communities that he hoped to impact and found them to be dismissive and despairing. By contrast, the children whom he encountered were enthusiastically receptive to dreaming and to working collaboratively to improve upon conditions in their communities. “If you want to start any kind of change, start it with the children,” Amlan suggests.

Filmmakers Maren Grainger-Monsen and Nicole Newnham artfully document the numerous and significant accomplishments of these young “revolutionary optimists” — to decrease malaria rates, increase vaccinations for polio, transform garbage dumps into playing fields, advocate for the rights of girls, and map their community — which in turn, results in the fourteen-year-old Salim being invited as a representative of his neighborhood to address the Indian Parliament, to lobby for potable water taps.

Inspired by the book, Mountains Beyond Mountains, Maren and Nicole set out to profile visionary heroes in global health. They were awarded a small grant for travel to Kolkata to attempt to film with Amlan and the kids at Prayasam, for what they conceived might be a short film. They were so captivated by the kids, that they ended up filming there over three-and-a-half years, producing a feature-length documentary, and subsequently collaborating on a number of offshoot projects in technology and community-engaged research and development.

At the beginning of the filming, when questioned about the purpose of her studies, eleven-year-old Sikha responds, “I will get … whatever is my fate.” Three-and-a-half years later, her thinking has transformed: if she does something good, she will be rewarded; if bad, she will not. “It is best to forget about fate,” she observes.

Sophia Stein recently spoke with directors and producers Maren Grainger-Monsen and Nicole Newnham about the making of The Revolutionary Optimists and their continuing engagement with Amlan and the Prayasam youth.

Sophia Stein: When you began filming The Revolutionary Optimists, Slumdog Millionaire had just come out, and people in the community did not like how they were portrayed in that film. How were you able to gain their trust?

Maren Grainger-Monsen: Their main complaint was that it was “poverty porn.” They felt like Slumdog Millionaire was highlighting how poor they were and sensationalizing it. Amlan spent a long time with us. For the first year, we only filmed in their tiny little clubhouse. After that, he gradually let us film out on the street, and then eventually, in people’s homes. But in the beginning, we weren’t allowed to film in anyone’s homes at all. We really had to earn the right to film.

Nicole Newnham: It was an interesting journey for us. From the beginning, we always had the goal of avoiding “poverty porn.” We always wanted to treat the subject area respectfully.

S2: What symbolizes “poverty porn” to you?

NN: Close-ups of dirt and cockroaches. Shots that make you pity people, because of their poverty.

MGM: Highlighting the lack of what people have.

NN: The whole point of the story we were trying to tell, was not that. We were trying to tell a story of strength and resilience and ingenuity and entrepreneurship. And yet, you had to give people that context to understand the struggle. So finding that balance was really challenging. We would show early cuts to people who would comment, “Well, I am not sure that I understand that they are poor because they are dressed so nicely, and they carry themselves so elegantly” — which is a whole interesting Western perspective that we had to wrestle with. So we tried putting in more context and facts and figures. Then slowly, working in partnership with our fantastic editors, Andrew Gersh in the Bay Area and Mary Lampson from the Sundance Documentary Edit Lab, we ended up deciding that the way to approach the story was to not worry about that, but rather to try hard to fundamentally humanize all the characters — so that people would stop worrying about all those questions that seemed to make them nervous in some of the earlier cuts. When we came to shoot in Salim and Sikha’s neighborhood, we were filming the kids’ work. Initially, I felt like there was this sort-of waiting, questioning — so when are you going to start to ask us about how much food we have and don’t have? We would come back, and we would still be filming the work. And we would come back again, and we were still filming the work. So staying focused on the work, which was all work towards improving their own community, eventually, people came to trust us.

S2: The film is beautifully edited; can you describe a bit about that process?

NN: At the Sundance Lab, we felt the weight of so many stories and characters — which is representative of Amlan and how he works. His vision is big! If we just focused on Salim and Sikha, it wouldn’t represent what Amlan is trying to do … and it probably would not have let Salim and Sikha’s story sing as much as it does. In order to tell the story and show the struggle, we needed different people to represent different things. It was an amazing process, and a long slog — because it was all in Bengali! We had to get all the Bengali transcribed … which sometimes you don’t do on a film like this, because it costs so much money and takes so much time. I think we blew through our transcription budget by about ten times. But there was no other way to do it. We would have ad-hoc translation from the incredible Bengali camera people that we worked with, who were filmmakers in their own right, and who sometimes would film things when we weren’t there — when some key scene was going to happen in Kolkata, and we were back in the Bay area.

S2: So how do you direct cinematographers from 7,000 miles away?

NN: We made a lot of trips to Kolkata and took a lot of years building up a relationship with Ranjan Palit and Ranu Ghosh, who are not just camera people, but filmmakers. If they had just been camera people, I think it wouldn’t have worked. They saw eye to eye with us. We would talk to them beforehand — this is what we think is going to happen, this is how we think it could play into the narrative, this is what we might focus on. But we had to give them the bandwidth to decide in the moment to shoot for the truth of it based on their understanding of our ultimate goal, which at that point was shared.

MGM: Their handheld work is really phenomenal. They were very intimate and able to get very close to people without disturbing them. It was quite surprising how they were able to float around. And they were just really easy-going people.

NN: Basically, Amlan was not going to let anyone come in and be a part of a filming team who was not going to also become a trusted part of the Prayasam family.

MGM: Ranu ended up doing several workshops for the kids — one on photography, and one on filmmaking. She actually got Sikha excited about making films, and now Sikha has gone on to make several films of her own and wants to become a filmmaker. That was really a turning point for the community, for their feelings about us and the project. There was a palpable shift.

MGM: We really weren’t filming the adults that much, so it was really how they perceived we were treating their children. The workshops had a big impact, I believe, because that was where they saw tangibly how we were interacting with their kids.

S2: The “Map Your World” project was outgrowth of the documentary?

MGM: While we were filming, the kids started creating this community map that’s in the film. We were really taken by that — that they were trying to take charge, to create their own map and put it up on the web. We thought about how it would be wonderful to add technology to the work that they were doing. So there is The Producer’s Institute for New Technologies at BVAC, pioneered by Wendy Levy, where the idea is to take a documentary film and then find new media technology to develop projects that come out of the film. We had this amazing experience, collaboratively with Amlan, in trying to figure out how to use smart phones and a multi-platform process to create these maps. Designing an application that allows kids to map their communities and create surveys, where they can collect data with GPS and time-stamped photos and then upload it to the database. Then it is all there on the map that you can see on their website. Or they can print it out and use it for the press and the government, to lobby for change. The kids are piloting several different projects in India now, and we are also working with groups here in the U.S.

NN: “Map Your World” is great because whenever we show the film to youth, it really causes them to experience a fundamental shift in their own identity as citizens in a community and as citizens of the world — as people who could be empowered to make a difference. It is fabulous to have “Map Your World” as a way to say, you don’t have to sit around and feel like: Geez, I live in such a privileged place. If these kids over in India are accomplishing so much, what am I doing?! You can say: “Hey, be a part of this community! Think about what you want to do. And here is a tool that can help you to do it!” And now Salim and Sikha and the kids from Prayasam, are teaching the kids in the U.S. how to do this community-engaged research.

S2: When you are working with these kids so closely, I imagine that you become very attached to them. As I am watching the film, I want to buy Kajal her sewing machine. But what is empowering about Amlan and the project, is that he doesn’t give them charity, rather he encourages them to dream and lift themselves out of poverty, to better their own situations. What do you believe is your responsibility to those kids who participated in service of your vision in making this documentary?

NN: We are working in partnership with Amlan to figure that out. It’s a really different role than you might think if you were going in and finding some extraordinary children and following them, and then the film is over, and you say goodbye. These kids have families and a mentor in Amlan, who is looking after them, and who is better able to judge what is a culturally appropriate and safe route for them to try to get out of poverty. Everything is such a delicate balance. If Amlan goes back to Kolkata and starts giving out money (that we or other people really would like to gift to a particular child), Amlan’s entire work could potentially be jeopardized — because then it’s this sort-of “STAR thing.” Amlan has worked for seventeen years to build a sense of alliance and organization and movement in Kolkata, through Prayasam. So the best thing that we think we can do is to get people to support Prayasam. We are trying to hook Amlan up with job training programs. To take the kids from: here you are an empowered change maker, but you are seventeen and out of high school, now what?

MGM: Amlan started a program called On-Track. He is trying to teach youth skills to transition out of school and into getting jobs. He is trying to teach them English, and computers, and how to write a resume, and be able to take the bus to an interview, and to actually be able to get jobs. It costs about $75.00 to sponsor one child for a year in the On-Track program. Amlan is having really good results. Melinda Gates did a TEDx exchange in Seattle where she showed the trailer for the film, and then had Salim and Sikha come onstage and talk with her, and they were both so incredibly poised, testament to the effectiveness of the Prayasam programs and training.

S2: Maren, your background is so unique: you’re a doctor and a filmmaker. And then you founded the program in Biomedical Ethics at Stanford. How did that all come to be?

MGM: I was an art history major in college, but I was always interested in the social issues of medicine. When I started medical school, it was definitely the social and ethical issues that I was interested in, not all the basic science. There were some classes where they would try to lead an ethics conversation, and they would read a little paragraph, and no one would have anything to say — there was no dialogue at all. Then they would show a film about something, and the class would erupt with all these opinions, because everyone had had this emotional experience. So I got a small research grant, and I took time off and made a short film in medical school. Then I got a rotary scholarship, and went to film school in London. Then I came back and finished medical school. So I have always gone back and forth.

S2: And what has your trajectory as a filmmaker been, Nicole?

NN: I have always been interested in how documentary film can treat the subject of art. I have also been interested in social justice. I made a film called The Rape of Europa with a couple of colleagues about the subject of Nazi art raiding and peoples’ efforts to protect the cultural heritage of Europe in World War II. I also made a film called “Sentenced Home,” which followed three Cambodian-American former gang kids who were suddenly eligible to be deported back to Cambodia after 911, when we forced that country to accept a repatriation agreement. It was a film about people who had come here as babies and were American, and didn’t know how to speak Kumai, and then they were suddenly thrown back and expected to fend for themselves. I think that Amlan’s use of art and culture to achieve social justice, and his unwavering belief in beauty and creativity, in a weird way, touches a lot of the themes that are in some of my other films. It has been incredible to work on this project with Maren and to feel that not only is this an incredibly artistic, powerful story, but to have a partnership with her to figure out a way to get it out into the world to specifically create change.

The Revolutionary Optimists opens in Los Angeles on April 19, 2013, and is rolling out to other cities nationwide. Click here to find information on screenings near you.

Photos, from top: Filmmakers Maren Grainger-Monsen (left) and Nicole Newnham; Amlan and the kids; Salim, pointing to a place on the map; Kajal carrying bricks.